The global economic and political landscape continues to provide a multitude of challenges for investors.

President Trump’s daily policy pronouncements, the prospect of Marine Le Pen winning the French presidential election in May and, with that, the possibility of France looking to exit the European Union (EU), and China’s ever-growing mountain of debt, are just some of the issues that investors need to consider. To add to that, US interest rates are on the rise and valuations of US stocks are at extremely high levels. We could go on and on. Yet, in the face of all these concerns, global stock markets have continued to move steadily higher!

At Platinum, it is our view that the very risks that investors become fixated on are often the source of the greatest opportunities. However, before elaborating on how we see these issues and others playing out for investors, it is worth reflecting on the key imbalances in the major global economies, which are not only driving investment outcomes, but also political outcomes.

Income Disparities - The Real Cause of Global Trade Imbalances

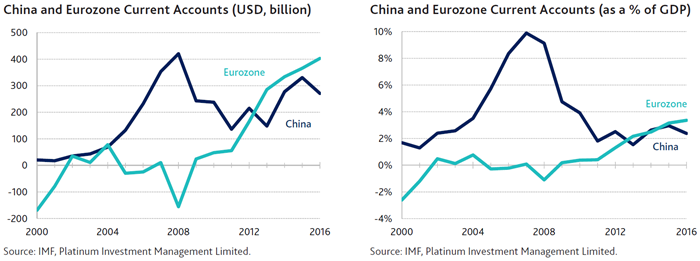

Most readers would be well aware of the massive trade and current account surpluses that China has produced over the last two decades as it became the unparalleled provider of low cost manufacturing of goods. Less well known is that China is not the only country currently running substantial surpluses. In the period post the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), the Eurozone has turned its current account deficit into a surplus in the order of US$403 billion, and South Korea’s surplus has risen fivefold to some US$100 billion. These provide a useful point of reference for China’s surplus of US$271 billion in 2016.

China’s substantial surplus is often attributed to the country’s advantages in terms of low labour cost as well as other variables such as cheap industrial land, weak environmental regulation, generous government subsidies, and an undervalued exchange rate. While all of these elements have certainly played a role in making Chinese exports competitive, the fact that the Eurozone and South Korea have substantial surpluses without the benefit of such advantages suggests that there is more to this story of trade imbalance. At the core of the problem in the surplus economies is the distribution of income. In China, the household share of GDP is unusually low, with household consumption expenditure accounting for only 38% of the economy. The other side of this equation is that businesses and government (more via state-owned enterprises than tax revenues) account for an unusually large share of GDP. This has served China well, as the corporate sector (whether privately-owned or state-owned) was behind the extraordinary investment boom that has driven China’s growth to date. But herein lies the problem! As the corporate sector exhausts its investment opportunities, with some capital-heavy industries like steel now facing contracting capacity, it will find its cash flows increasingly exceed its capital expenditure needs.

These savings of the corporate sector are the source of China’s trade surplus, as they remain in the hands of those who have no way of spending them. Imagine for a moment if these excess funds were instead in the hands of Chinese households rather than a narrow group of private and public shareholders. They would likely be spent on housing, autos, and a range of consumer goods from handbags and shoes to holidays. Moreover, while a good proportion of these goods and services would be domestically produced, there would also be a significant element of imports, such as aircraft, semiconductors, overseas travel and the like, which would drive down the trade and current account surplus. Such a consumer boom would itself engender significant investment in a range of industries, not only in China, but globally. It is for this reason that we focus intently on the Chinese consumer – this sector of the economy must prosper if China is to continue its rapid development and transformation.

The income inequality between China’s corporate sector and households is also present in the developed world, but there the inequality is more evident in the distribution of income across households. Between 1994 and 2014, the real income of the top 20% of households in the US grew by 16% while the bottom 20% experienced a 4% decline. The growth in income for the majority of US households initially resulted in a consumer boom which was reinforced by the draw-down in home equity via mortgage refinancing until 2008. However, this boom in consumption, together with the resulting debt burden, left the American consumer with little appetite for further spending. Indeed, since 2008, as income further accrued to middle income and wealthy households, debt repayments and savings have become the focus. As is in China, income is accruing in the hands of those less likely to spend. If this trend in income disparity were reversed, lower income households would likely display a much higher propensity to spend, not only boosting total consumption, but potentially creating new investment opportunities as well. The rise in income inequality experienced by the US can be observed across most of the developed countries, though the redistribution mechanisms of taxation and government spending have generally been more effective elsewhere, leading to less extreme outcomes.

Interestingly, though, while income inequality has resulted in substantial trade surpluses for China and, for that matter, Germany and South Korea, the United States saw the opposite outcome. To examine this issue we need to consider two important relationships that exist in all economic systems. The first is that a current account surplus will always be exactly offset by a capital account deficit. When China, Germany and South Korea run current account surpluses, they are exporting their excess savings via the capital account to economies that run current account deficits, such as the US, the UK and Australia. The other key relationship to consider is that in a closed economy, all savings will be invested. Savings by definition always equal investment. Thus, in the global economy, which is most certainly a closed system, the excess savings of the surplus countries will be invested elsewhere.

The export of excess savings by the surplus countries has been a key to many of the boom-and-bust scenarios seen around the globe. In the years leading up to 2008, these excess savings found their way into the US housing market, in the first instance driving up investment in housing. The secondary effect, though, was to allow households to draw down on their home equity to consume more of their income, thus balancing the investment and savings equation globally by reducing savings in the US. The next destination for the surplus countries’ excess savings was investment in the resources sector, notably here in Australia and in unconventional energy resources in the US and beyond. In recent times we have seen these funds finding their way into residential apartments in Australian capital cities and other major cities around the world. The most notable destination, however, has been financial assets. US bonds, shares and property, seemingly attractive as a relatively “low” risk destination, have been key beneficiaries of these excess savings looking for a home.

It is in this context that one might see that the trade surpluses President Trump rails against are a function of more than just export competitiveness and protectionism. Excess savings in places like China enabled US households to increase their spending (via home equity draw-downs), thus creating the relative trade positions of the two countries. Had the Chinese been big spenders and their current account turned to deficit, there might perhaps have been a reversal of roles.

A Possible Rebalancing May Be Under Way

The Health of the Chinese Consumer

Equipped with this understanding of the interplay between global trade imbalances and income disparities, we can now examine some of the forces that have been influencing markets and causing investors concern.

The one place where there is good news, and thus great opportunities for investors, is China. As explained above, one of the main causes for China’s excess savings has been the income disparity between households and the rest of the economy. Ideally, one would hope to see household income growing faster than the economy as a whole and government policy generally favouring such an outcome.

It is not always easy to observe such changes from China’s government statistics, but there are numerous signs showing that the Chinese consumer is doing well. Foremost amongst these is the ongoing strength of residential property sales. While the volume of property sales has fluctuated over recent years, the downturns have primarily been in response to government initiatives to curb speculation. When restrictions are removed, sale volumes have typically rebounded strongly. 2016 saw sales of approximately

16 million apartments, compared with the previous peak of 13 million in 2013. While these volumes are enough to cause consternation amongst foreigners, the cumulative volume of apartments sold since 1999, when private ownership of residential property was first legalised, is in the order of

130 million. Essentially, this represents the entire modern housing stock of the country. For the 400 odd million households remaining in communist era housing, it remains a question of affordability. Nevertheless, considerable latent demand for new housing exists. It is also worth noting that mortgage debt, while now growing quickly, is only at about 36% of China’s GDP, and that buyer surveys have continually estimated that owner-occupiers account for 85% to 90% of all apartments sold.

The auto market is another health indicator for the Chinese consumer. Throughout China’s economic slowdown over the past few years, the passenger vehicle market has continued to grow. Vehicle sales have grown steadily from 15.5 million in 2012 to 24.4 million. As auto finance is not broadly available, 80% to 90% of these purchases are paid for with cash. There is ample evidence that the Chinese consumer is in good health, which is all the more impressive given that millions of jobs have been lost in the construction and related sectors in recent years. Government policy is generally supportive of higher household incomes. In particular, we would note rural reforms and wage hikes for government workers as examples. The bigger driver, however, is likely to be the relatively fully employed workforce that continues to experience healthy income growth.

China’s Debt Problem

Few observers would likely challenge our view that the Chinese consumer is in good shape. The issue that concerns most is the ongoing growth of China’s debt level, with the broadest measures growing by 14% in 2016, reaching 256% of GDP. An examination of the available data indicates that the growth in the use of credit is predominantly attributable to state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which raises the question of whether these funds are being applied productively. Some Chinese banks indicated at our recent meetings that the principal target for their lending to the SOEs is government sponsored infrastructure and related projects. However, fears remain that this credit is being used to prop up loss-making ventures in order to maintain employment. We think the truth is likely to be a combination of both. To the extent that loss-making ventures are being supported, this ultimately is a form of fiscal spending by the government and one should treat any such loans as part of the budget deficit. It is worth noting that last year’s supply side reform in the coal and steel industries saw capacity closure, loss of jobs, and significant improvements in profitability – a signal that the government no longer readily accepts the status quo of loss-making SOEs. We would also add that many SOEs are profitable and, as such, are an asset on the government’s balance sheet. Ultimately, without greater transparency, there can be no clear conclusion to this discussion. However, we would note that the overall position of government finances in China is extraordinarily strong, and the current debt level is likely to be sustainable for some time.

What all of this means for China is an economy where the consumer sector becomes more prosperous, an aggressive infrastructure building program provides another source of growth in activity, while heavy industry, dominated by SOE ownership, continues to muddle through. In this case, China will ultimately outgrow the problems caused by its investment boom, much as the US has done post its 2008 collapse. Of course, the banking system will continue to experience nonperforming loans, but these are an accounting entry for losses that have already been incurred. However, this pattern of development will likely see China’s trade and current account surpluses decline, a process that has already begun in 2016 when the surplus fell by almost 20%.

Proposed Policy Changes in the US

A declining surplus, as per our earlier discussion, will see China’s export of excess savings decline. Before we ponder the implications of this trend, however, it is worth considering the policy changes that have been proposed in the US. It is quite possible that some of the changes proposed will be “positive” for the stock market in the short-term, though are ineffective economic policy. Take, for example, the simple case of a corporate tax rate cut. There is no question that a lower tax rate will initially increase the earnings of companies, all else being equal, thus making them more attractive to investors. The real question is whether these additional funds will encourage US companies to invest more in the US. To some extent one imagines they will, but US company profitability has never been higher than it is today, yet, investment remains subdued. If the current pattern of corporate behaviour were any guide, companies will likely pass additional earnings onto shareholders through dividends and share buy-backs. Such a result will reinforce the income inequality by funnelling more income to the highest income groups in the economy who have a low propensity to consume. Similarly, the failed repeal of Obamacare, had it succeeded, would have taken benefits away from the lowest income households, a group with a high propensity to consume.

A variety of measures have been floated to reduce the US trade deficit, from a border adjustable tax system to straight tariffs on imports. Some high level observations can be made. Firstly, if at the core of the global trade imbalances are, as we have suggested, the excess savings in China, Europe and South Korea that are a result of income distribution in these countries, the solution is unlikely to be found in trying to reduce imports. Indeed, when one looks at the extraordinary ecosystem of product design, prototyping, manufacturing, packaging, shipping and logistics found in China’s Pearl River Delta, one quickly realises the impracticality of the idea of moving manufacturing back to the US in any meaningful way. According to one contact in one of our recent meetings, manufacturers in the apparel industry who have moved production to Vietnam or Bangladesh still ship their products to China in order to take advantage of the existing supply chain before shipping to Europe or the US. It will be harder than simply finding 25,000 workers in one location to take on the work. This is not to say that tariffs will not reduce the trade deficit, but that it will do so by reducing income (and thus savings) in the exporting countries. The US consumer will face higher prices for a wide range of imported goods, and inward capital flows will decline.

The one policy that the US administration has proposed that has the greatest potential to improve the country’s outlook is increased investment in public infrastructure. As we have stated, America’s trade deficit has resulted in offsetting capital inflows, but the problem has been finding a productive investment for these funds. Investment in public infrastructure is one possibility. However, a practical challenge is the lack of consensus among the various factions within the Republican Party on these issues and the questionable competence of the new administration. It should be remembered that changing any system, no matter how well thought-out and well-meaning, will always involve a loss to entrenched interests who will fight the changes to the bitter end.

Political Risk in Europe versus Economic Recovery

In France, the consensus among political commentators is that, while Marine Le Pen will make the final run-off for the presidential election, she is unlikely to win the election. After Brexit and the election of Trump in the US, the confidence of markets in such political forecasts is understandably low.

A Le Pen victory will, at a minimum, create significant uncertainty about France’s ongoing position in the EU and the Eurozone. Even if Le Pen does not win, the cloud of uncertainty will not entirely go away as all will be examining the ramifications of the German elections in September and the Italian elections in 2018. With investors focusing on the political risk in Europe, what is not being widely discussed is how the EU’s economic recovery is steadily making progress. Between 2008 and 2012, the Eurozone countries lost five million jobs. Since 2012, employment has grown strongly with almost 10 million jobs created with another million added in 2016. Meanwhile, across Europe auto sales and property prices are approaching their pre-2008 levels, and there are signs that demand for credit is starting to rise. There is a possibility that better economic conditions in Europe will begin to reduce the anti-EU/anti-Euro sentiment that is present in parts of Europe. One might also reasonably expect that stronger economic conditions will see stronger personal consumption, leading to stronger imports and peaking in the region’s current account surpluses.

Markets

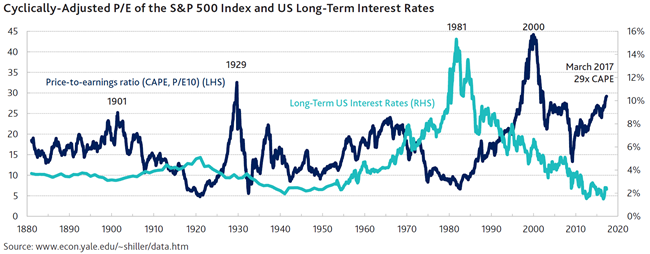

The key risk for markets that we are yet to address is rising US interest rates. The US Federal Reserve has slowly started the process of lifting interest rates, with the discount rate increased three times over the last 15 months and now standing at 0.75%. However, it should be remembered that we had been through a period of unconventional monetary policy with quantitative easing (QE). Economists who have modelled the impact of QE suggest that it was worth 2% to 3% of rate cuts. In other words, the effective discount rate was -2% to -3%, and thus, with the removal of QE, the US economy has experienced rate increases equivalent to 2.75% to 3.75%. While this modelling may not be entirely reliable, the point is that we are probably further into a monetary policy tightening cycle than the headline figures suggest. While the US economy and stock market tend to be immune to initial increases in interest rates, ultimately, it will reduce growth and profits, and with that the market falls. There is probably no more reliable correlation between the stock market and economic variables than the one it has with interest rates.

In the meantime the US economy continues to show improving strength with the labour market, on some reckonings, as strong as it has been since the 1970s. Of note is that over the last three years the lowest income households have been seeing their income grow faster than the average. Add to this the boost to consumer and small business confidence from Trump’s election win and you have conditions that should continue to underpin economic growth. Of course, ongoing good economic conditions may well encourage the Fed to keep increasing interest rates. This is a dangerous situation when combined with the fact that the US market is trading on a valuation that is high by historical standards. Indeed, the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio[1] of the S&P 500 Index has only been at this level or higher in 1929 and 2000, on the eves of the Black Tuesday crash and the Dot Com Bubble burst respectively. While predicting the timing of any sell-off is problematic, the risk of a large sell-off is rising. What could detract this in the short-term is a significant cut to the corporate tax rate. Across our funds at Platinum, we have maintained a relatively low exposure to US stocks, particularly relative to benchmarks and the majority of other managers.

The French election clearly represents a risk to markets, but these types of risk are not easily managed. Usually ahead of such events investors position themselves in a way that results in unanticipated market moves even when the undesirable outcome transpires. With Brexit, while the stock market sold off briefly after the event, it has rebounded significantly and is almost 15% higher today than it was on the day prior to the vote. However, the British pound did take a battering and remains almost 20% lower. With the US election, many investors had expected a significant sell-off in the event of a Trump win and were caught out badly as the market rallied strongly when the event happened. Directly playing these types of outcomes is a difficult game and such speculative strategy is not part of Platinum’s approach. We would simply note that our French holdings are multinational consumer product or drug companies whose fortunes are relatively immune to local conditions. In addition, holding cash in the portfolio allows us to take advantage of any sell-off that may occur.

Outlook

In the years since the GFC, investors globally have craved certainty, and this has driven a preference for perceived low risk assets such as bonds and, in the equity markets, stable earning assets such as consumer goods, real estate and utilities (often referred to as “bond proxies”). Conversely, investors have sought to avoid the uncertainty associated with companies, industries and countries facing any challenges or cyclicality. We think this is precisely where the opportunity for investors lies. The valuations of stocks in China, South Korea, Japan and, to a lesser extent, Europe, remain at attractive levels. Of course, these regions have the very elements of uncertainty and cyclicality that investors have wished to avoid. We are of the view that improving economic conditions in these major economies outside of the US presage a greater willingness by investors to take on this perceived risk, thereby taking advantage of the better returns on offer in these markets. This process has already begun in the second half of 2016 with improving performance in emerging markets, cyclical and financial stocks, and rising yields on bonds.

In the longer term we could potentially be entering a period where a significant rebalancing of global current and capital accounts substantially changes the dynamics of global capital flows. In China, this will in part be a natural consequence of the consumer economy taking hold, but likely also requires reform that redistributes income towards the household and away from the state. In Europe and elsewhere, the surpluses may recede as cyclical recovery strengthens and the pressure builds for fiscal spending to redistribute income within these economies. Such a rebalancing would be a healthy outcome in aggregate for the global markets and economies; however, the removal of capital flows from areas that have unduly attracted capital may result in some dramatic adjustments.

[1] The cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (or CAPE ratio) is current price divided by average earnings per share over the last 10 years, adjusted for inflation.

DISCLAIMER: The above information is commentary only (i.e. our general thoughts). It is not intended to be, nor should it be construed as, investment advice. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Before making any investment decision you need to consider (with your financial adviser) your particular investment needs, objectives and circumstances. The above material may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Platinum Investment Management Limited.