Global stock markets have recognised the synchronised growth and improving prospects across all the major economies, and have rewarded investors with strong returns over the last 12 months. While some commentators are raising warnings about stock market bubbles, it is our assessment that, despite the recent good outcomes, most investors remain cautious when it comes to the prospects for future returns from owning shares.

As we enter 2018, the global economy appears to be in as good a shape as it has been any time in the last decade. The US, Europe, China and Japan have each shown improving economic momentum over the course of 2017. Higher commodity prices, we believe, should bring about stronger growth in many of the emerging economies in the year ahead. Interestingly, the trends in place today (excepting the run up in commodities) were obvious enough a year ago, though at the time investors and commentators were preoccupied with a range of concerns.

The US, which has led the global recovery since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), continued to grow strongly in the final months of 2017. Consumers appear to be in good shape as employment markets remain strong which, together with the promise of tax cuts coming in 2018, saw consumer confidence reach levels not seen in almost 15 years, well before the GFC. New home sales, which have been relatively slow to recover in the current cycle, are now experiencing sturdy growth. To date, there has been little evidence of rising inflation and, as such, while interest rates are rising, they do not look to be a threat to economic momentum for the moment. While the delivery of the tax cuts is a new impetus for growth (though we suspect not a significant one), the picture is not very different to that of a year ago. A year ago, the great concern was the proposed policies of the newly elected President Trump: the roll-back of the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) which threatened to leave potentially 20 million Americans without health insurance, a possible trade war with China, and a major revamp of the tax system that contained more sound and fury than legislative detail. Of course, little has come to pass other than a much reduced tax plan; meanwhile the economy has continued to motor along.

In Europe, employment growth is strong and consumer and business confidence is high and rising. Today, economic growth rates across Europe are back at pre-GFC levels. A year ago, the improvement in Europe’s economic performance was already well established. The strength of the job market today is simply a continuation of the upward trajectory that had already started then. However, a year ago all were concerned with political instability in Europe post the Brexit vote and the defeat of the Italian constitutional reform referendum. There was much discussion about the possibility of Marine Le Pen winning the French presidential election and the implications that would have for the sustainability of the European Union (EU). Concerns also remained with regards to unresolved bad debts in the European banking systems, particularly within Italy. What came to pass was a surprisingly positive outcome in the French presidential race with pro-reform candidate Emmanuel Macron claiming victory. Bad debt issues have either been resolved or have faded to the background.

Throughout 2016 China staged an impressive economic recovery from its investment downturn, kick-started by government spending on infrastructure as part of its “One Belt One Road” program. The residential property market recovered and excess inventories were well on the way to being cleared. Despite this clear improvement in the economic environment, there remained much scepticism at the beginning of 2017 as to whether the recovery was sustainable, with most concerns focused on the level of indebtedness in the economy and the potential for a bad debt crisis in the banking system. While these were not unreasonable concerns, as we first discussed in our March 2017 Macro Overview and then in more detail in the September 2017 Macro Overview, China’s supply side reforms were dealing with issues of excess capacity in industries such as coal and steel. The result was immediate improvement in profitability and, with that, the ability to service debt. Over the course of 2017 these supply side reforms have been extended, particularly with respect to enforcement of environmental standards, leading to further improved profitability across a wide range of industries both within and outside of China.

While the fears regarding China’s indebtedness have receded somewhat in the second half of 2017, investors and commentators generally remain sceptical. Along with the supply side reforms, there have also been reforms of the financial sector, in part to address the reckless use of credit in the system. It is somewhat ironical that these changes, both of which act to limit the state’s role in the economy, are viewed as evidence that President Xi is steering the economy back towards central planning and away from markets. Our observation is that all the signs point in the other direction. Indeed, if one looks at the electric vehicle (EV) market in China, the mechanism being used to encourage auto producers to sell EVs is essentially a simplified version of the mechanism employed by the EU, only that it will be implemented in China a year or two sooner. Besides, the auto industry, like most of the other fast growing industries in China, is dominated by private companies operating in a predominantly free market.

Finally, there is the world’s third largest economy, one that is almost forgotten by investors after 25 years of deflation, slow growth, and falling asset prices. The list of woes that usually attract attention when Japan is mentioned includes massive government debt, the extraordinary printing of money by the Bank of Japan (BOJ), and a rapidly aging population, to name just a few. Yet, the country is currently enjoying record levels of employment, driven by rising participation in the work force by women, and rising wages. Corporate profit margins are at record highs. And, for the record, the economy has not seen such robust levels of growth for more than two decades!

The world has not seen this degree of synchronised growth across the major economies since 2008. Together with the supply side reforms in China, this growth has helped to drive a range of commodity prices higher during 2017. Over the next five years, an additional factor driving demand for various metals will be electric vehicles. Combined with a lack of investment in new supply in recent years, this should see commodity prices remain buoyant. While it may act as a tax on most of the developed world, this transfer of income to large emerging economies such as Indonesia, Brazil and Russia should be beneficial for overall global growth.

What are the key risks to this buoyant global outlook? The obvious risk, and one that the markets are focused on, is a return of inflation. In particular, labour markets are tight in the major economies, with the exception of Western Europe, so higher wage inflation is certainly possible if growth remains strong. Couple this with higher commodity prices (and the anecdotal evidence of shortages in a range of industrial and electronic components), a scenario of rising inflationary pressures cannot be dismissed. If central banks were to raise rates in a sustained and steady fashion in response to inflation, given the level of debt carried in all the major economies, it would certainly pose a threat to current rates of growth.

The other great unknown is the longer term ramifications of the money printing exercises by the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the BOJ. While the US, on face value, has extricated itself successfully from its quantitative easing (QE) program (i.e. it has stopped “printing money” via bond and other asset purchases), it is yet to attempt to unwind this policy in any meaningful way. For the moment, QE continues in both Europe and Japan.

Market Outlook

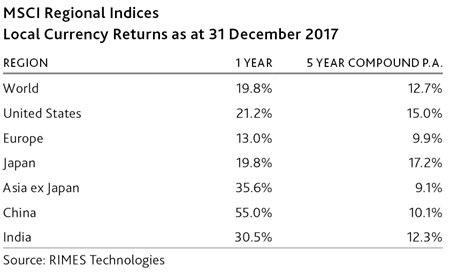

Global stock markets have recognised these improving prospects and rewarded investors with good returns over the last 12 months. The following table shows the 1-year and annualised 5-year returns in local currency terms for key global markets.1

The 1-year returns presented here would usually suggest that one should be cautious about the prospects of future returns. However, the 5-year returns, while solid, are not spectacular except in the case of Japan and the US. Japan, it must be remembered, started the period at the bottom of a 23 year bear market!

It is our assessment that, despite these good outcomes, most investors remain cautious when it comes to the prospects for future returns from owning shares. We see this in the frequent headlines carrying warnings from investment experts for overvalued stocks, stock market bubbles, and even the looming possibility of another GFC. We also see this caution in the actions of investors around the world where we still observe a strong preference for other asset classes, notably debt securities. This assessment, together with the fact that we continue to find new companies to buy at attractive valuations, makes us cautiously optimistic that we are well positioned to continue to generate good returns for investors over the next three to five years, if not in the next 12 months.

Interestingly though, despite caution around share markets, the rise of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies shows that enthusiasm for speculation is far from dead! I would encourage anyone with an interest in this topic to read Sava Mihic’s excellent article Bitcoin – A Primer. Certainly, some cryptocurrencies look on face value to be another old-fashioned bubble, though they may still have some way to go despite the daily predictions of their demise. Could an eventual burst of the bubble have the potential to cause disruptions to broader financial markets? Perhaps, particularly if significant amounts of debt are involved, though for the moment this appears unlikely. For every loser in this speculative game, there is an offsetting winner. Perhaps a more likely scene for a significant financial accident may be the debt markets, where the risk aversion of investors, together with the QE policies of central banks, has driven yields to extraordinarily low levels.

1. For Australian investors, the returns in most cases would have been significantly better over 5 years due to a weak Australian dollar, but weaker over the 1 year period as the Australian dollar has appreciated against most currencies over the last 12 months.

DISCLAIMER: The above information is commentary only (i.e. our general thoughts). It is not intended to be, nor should it be construed as, investment advice. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Before making any investment decision you need to consider (with your financial adviser) your particular investment needs, objectives and circumstances. The above material may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Platinum Investment Management Limited.