Markets are currently positioned in a very defensive manner, concerned by a potential slowdown in China, the ongoing US-China trade war and rising US interest rates. CIO Andrew Clifford examines each of these issues and reminds us that it often pays to head in the opposite direction from the crowd.

US-China Trade Tension

The trade war is the issue that has been preoccupying investors over the last quarter. At the end of June, the US applied a 25% tariff on US$50 billion of Chinese imports, and followed up in late September with a 10% tariff on a further US$200 billion of imported goods from China. And of course, President Trump has tweeted that he will put tariffs on all remaining Chinese imports if they don’t toe the line. China has followed suit and has now applied tariffs on almost the entirety of their US$130 billion worth of imports from the US. The questions that arise are “for how long will this go on” and “what is the impact on the economy and markets”.

The consensus view is that President Trump will not back down and that on the trade issue he generally has bipartisan support. It is also expected that China will not passively accept the US actions and will continue to respond with countervailing measures. The conclusion of this consensus view is that we are entering a new era of rising protectionism and trade friction. The problem for investors is that, when faced with a political issue such as this, no amount of reference to any logical reasoning will provide one with a definitive answer as to what will happen. One can only try and assess the significance of what has happened so far and attempt to make observations about possible outcomes.

The obvious place to start is to consider the importance of trade to both sides in this dispute. For China, exports to the US, totalling US$505 billion, represent around 4% of GDP, and so far approximately half of these exports are subject to tariffs of 10% to 25%.[1] While this will lead to some loss of economic activity in China, there are a number of reasons why the impact will be well short of losing the entirety of these exports.

Firstly, one would expect the exchange rates to move, offsetting in part the price rise for US buyers, and indeed the Chinese Yuan has depreciated 8% against the US Dollar since April this year. Of course, the US administration may accuse the Chinese of currency manipulation, but as China’s foreign exchange reserves have remained stable, the accusation will be difficult to substantiate.

Many goods will be difficult to source from other locations. An interesting article in The Wall Street Journal cites a study on the value added in smartphones which found that the Chinese labour cost in the assembly of iPhones accounted for as little as 1% of the finished product’s value.[2] The study concluded that assembly of such phones in the US would raise the price to the end consumer by approximately US$30, a fairly small increase relative to the total retail price ranging from US$449 to US$1,099. However, to transfer the assembly of US-bound iPhones to the US would require finding approximately 60,000 workers. The article cites the example of Motorola who, in 2013, wanted to assemble a line of its smartphones in the US, but ultimately couldn’t source the labour. And this won’t be the only challenge. Chinese assemblers are able to rapidly find large numbers of labourers as production ramps up for a new product launch, and then lay them off when volumes recede. The benefit of Chinese assembly is not just the slight improvement in cost, but also the extraordinary flexibility in production that it brings to the smartphone producer, something that labour laws in most parts of the world, including countries such as Indonesia and India, simply do not allow.

Of course, some Chinese production will move to other low cost locations such as Vietnam and Mexico. However, many lower value-add activities, such as textile and shoe manufacturing, have to a large extent already migrated to alternative locations. While this may reduce the US’s trade deficit with China, it is unlikely to substantially change the country’s overall trade imbalance. Indeed, returning to the smartphone example, the same study showed that key components for the iPhone are sourced from Japan, Korea, the UK, Taiwan, the Netherlands and the US! Moving where final assembly occurs will hardly shrink the size of the US deficit by very much.

To the extent that the US and China are unable to find substitute sources for their imports, then, the tariffs will either be passed on in higher prices or reduce the profit margin of the supply chain, or a combination of both. There does remain the potential for many unintended consequences. As we highlighted in our June Macro Overview, the application of tariffs on imported steel and aluminium had left US companies at a disadvantage when competing with offshore producers not just in their home market, but also in export markets. However, if we simply treat the tariffs as a tax on the US economy and assume that the announced tariffs are collected on the full US$250 billion of imports, they will amount to approximately 0.16% of US GDP, a paltry amount particularly when compared with the individual income and corporate tax cuts passed earlier this year, which will amount to 0.9% of GDP per year in the first four years.

The initial conclusion, based on the actions taken by both the US and China to date, is that the impacts are likely to be relatively small across the broad economies of both countries. The concern, of course, is that it may not stop here. Indeed, the last round of US tariffs on US$200 billion of Chinese imports will rise from 10% to 25% in the new year if China doesn’t accede to US demands, and President Trump has tweeted that he will apply tariffs on all Chinese imports, if necessary. Indeed, why stop at 25%? Why not 50% or 100%? Perhaps it is all part of the theatre of the US mid-term elections that will be held this November, but who would know!

Meanwhile, the discussion from the US side has shifted from the size of relative trade deficits and surpluses to the alleged intellectual property theft and forced technology transfer by China. This change of focus is hardly surprising. As we enter 2019, the proponents of the trade war will need to start explaining why their trade deficit hasn’t at least fallen to some extent with the imposition of tariffs.

The question of technology transfer is an interesting one. It has no doubt been a central part of China’s industrial policy to require foreign companies wanting to access its domestic economy to set up local production, usually with a local partner. In this way, general know-how is gained by local employees who may ultimately end up enabling new local competitors. Of course, there are also examples of more blatant theft of proprietary intellectual property, which can be difficult to prove, particularly when the local legal system in unlikely to be especially helpful to the foreign partner. So the issue of intellectual property does appear as one that may be fought over and may well cause some friction in the foreseeable future.

But even this debate of “IP theft” seems to be a futile exercise. Arguably no foreign company is “forced” to transfer its technology to China or a Chinese joint venture partner, that the choice was always there to not enter China, though many chose the path. The rationale is simply down to the traditional market forces of competition. You either did it or stood by while watching your competitor move its operations to China and gain an immense advantage through higher profits and greater scale.

The automotive market is the perfect example. China’s passenger vehicle market is now the largest in the world, 40% larger than that of the US,[3] and for the foreign OEMs with strong positions in the market, such as GM, Volkswagen and BMW, it represents as much as a quarter to a half of their profits.[4] In recent years, local producers have been gaining back market share as the quality of their products has improved significantly, as demonstrated in quality surveys by the likes of JD Power. The ability of the local players to improve their products is a function of the broadening “know-how” within China, which undoubtedly is a result of a strong local industry led by the foreign players. Indeed, a significant local components industry has developed, which now exports nearly US$17 billion of auto parts to the US.[5]

Has there been any misappropriation by local Chinese companies of foreign OEMs’ or their suppliers’ proprietary intellectual property? Almost certainly yes. But even in the “wild wild east”, suppliers stealing IP would be excluded by foreign OEMs and from the export markets of developed countries. It is also worth observing that leading local auto producer, Geely Automobile, most certainly uses foreign “intellectual property” and know-how in its production. Its method of accessing this know-how was to acquire a struggling western auto producer, Volvo. Today, M&A is the way through which the best Chinese companies are acquiring technology and know-how, as seen in a plethora of transactions from Midea Group (Chinese household appliance maker) buying Kuka AG (German robotics and automation supplier) to Weichai Power (Chinese heavy duty Diesel engine maker) buying a controlling stake in Kion (German supplier of forklifts and warehouse systems).

Finally, it is worth noting the following investment projects by foreign companies in China, all of which have been announced since the beginning of July this year: BASF of Germany announced a US$10 billion chemical plant in Guangdong province, ExxonMobil of the US a US$10 billion petrochemical plant also in Guangdong, and Tesla a US$5 billion plant in Shanghai. Each of these investments is to be fully owned by the foreign company, which typically is not permitted in the industries concerned. These announcements suggest that the Chinese have already begun to modify their approach and that major foreign companies remain confident to invest in the country.

So while the differences between the US and China on the issue of trade seem intractable, the question is “what really can be done”. The opening-up of China to foreign investment and trade has allowed the likes of Apple, BMW and Nike to earn enormous profits, and has given consumers access to new technologies and affordable running shoes. The system has delivered massive benefits to businesses and consumers across the globe. This is the hard economic reality that policy makers face. While they may be enjoying the political theatre of it all, the current pathway of ever rising tariffs, if continued, will simply result in lower consumer spending power, lower profits, and a loss of jobs, in both countries. This should provide both sides to the dispute with a compelling reason to start looking for solutions once the noise and excitement of the fight dies down. The drama may take some time to play out and no agreement is yet forthcoming, but ultimately a negotiated resolution seems to be a more likely outcome than returning to a trading system akin to that of the late 1970s and early 1980s with commensurate falls in global living standards.

Other Developments

While the verbal battles of the trade war raged on, there have been some significant ongoing developments elsewhere that need consideration.

As we have discussed in our March and June Macro Overviews, China has been implementing a significant reform of their financial system, bringing the shadow banking activities back onto the balance sheets of the banks. This has resulted in a tightness in credit availability during the first half of the year, which has led to distress in some parts of the economy. Notably, peer-to-peer lending networks[6] have come under pressure, and as a result individual lenders have suffered losses from investments in these loans.

The concern is the potential impact the credit tightening will have on consumption expenditures. Indeed, July and August monthly passenger vehicle sales in China are down 5.3% and 4.5% respectively from a year ago. Into this potentially weaker economic environment, then there is the issue of the impact of the trade war on business confidence where, unsurprisingly, there is evidence of a cutback in investments by the manufacturing sector. Softness in infrastructure spending was also evident in the first half of the year as local governments faced a lack of funding following tightening measures directed by the central government.

Investors are concerned that a more generalised slowdown may have begun in China. Whether that is in fact the case remains debatable. Construction activity remains strong, as are sales of residential property. Steel production remains at near record levels. Nevertheless, Chinese policy makers have acted pre-emptively, presumably concerned by the potential impacts of both the trade war and their own financial reforms. Initiatives include extending the time frames for banks to bring back shadow banking assets onto their balance sheets, and granting approval to roll over existing loans. Funding for approved infrastructure projects is being made available. Tax cuts for individuals and businesses worth 1% of GDP[7] have been announced. While these and other measures may seem far more modest than the stimulatory policies put in place during previous periods of economic weakness, it is also the case that, for the moment, the softness in the economy is not as apparent as it had been in past cycles.

The US economy continues to grow strongly, helped along by the tax cuts put in place this year. Employment remains robust, consumer and business confidence is high, and while inflation is on the rise, it remains at relatively subdued levels. During the last week of the quarter, the Federal Reserve increased interest rates by 0.25% for the seventh time this cycle (since late 2015), bringing the federal funds rate to 2.25%. As we have stressed in past reports, while rising rates will eventually bring an end to the current economic cycle, it is difficult to assess when the impact of higher rates will be felt. Conventional rules of thumb, such as the steepness of the yield curve, do not suggest any imminent downturn.

In Europe, growth has slowed through the first half of the year as the region deals with the UK’s messy exit from the European Union (EU) and concerns around the economic policies of the new Italian government. However, as outlined by Nik Dvornak in the Platinum European Fund Report, the region continues to grow employment with 2 million jobs added over the last year, and with countries across the EU close to achieving fiscal balance, there remains capacity for their governments to increase spending. Further, a current account surplus of 3.5% of the Euro Area’s GDP places the region on a strong footing for future growth.

The Japanese economy also remains in good health. Employment is strong with 1.1 million jobs added in the last year, and the ratio of open positions to applicants is running at 1.6, the highest level in 43 years. Wages are growing at just over 2% per annum. There is potential in the country, and many businesses still have excess labour. If higher wages can attract labour into more productive endeavours, the benefits to the broader economy could be quite significant. As Scott Gilchrist points out in the Platinum Japan Fund Report, Japan's labour costs are now globally competitive which should underwrite ongoing investment. Finally, it is worth noting that nationwide land prices registered the first increase in 27 years.

Market Outlook

The potential of a China slowdown, exacerbated by the trade war, and the impact of ongoing rate rises in the US, have seen investors once again become risk averse. Specifically, this has meant avoiding companies that face any degree of uncertainty and focusing instead on companies that are perceived to be immune from external factors like trade tariffs. Often this is expressed by commentators as a preference for “growth companies” over “cyclical businesses”, but many more companies have been caught up in the sell-off than the traditional cyclicals, extending to sectors such as financials and lower-growth technology stocks. The exception has been energy stocks which have been helped by higher oil prices over this period.

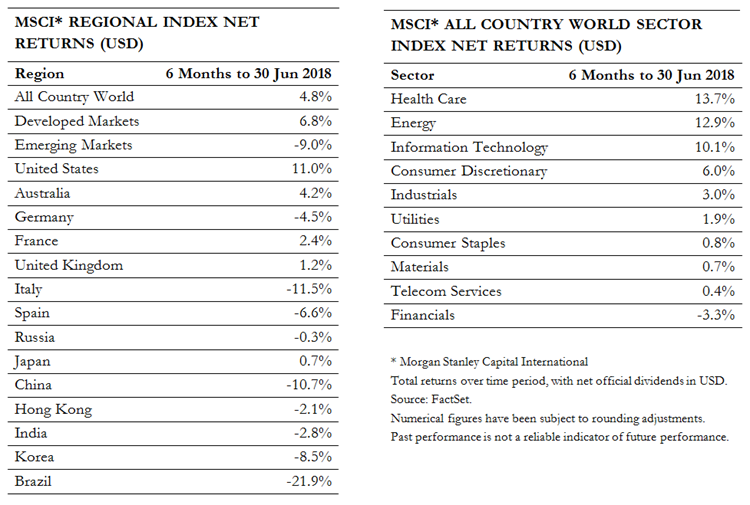

Geographically, this has translated into significant outperformance by the US market as it has a much higher representation from those strongly performing sectors than the rest of the world (the technology, healthcare and energy sectors together account for more than 47% of the MSCI US Index, compared to approximately 28% for the MSCI AC World ex US Index). Generally, the weaker geographic markets have been those with a greater weighting in cyclical and financial stocks throughout this period. Additionally, the emerging markets have suffered as a result of the stronger US Dollar increasing the cost of funding for external debts, most notably in the case of Turkey.

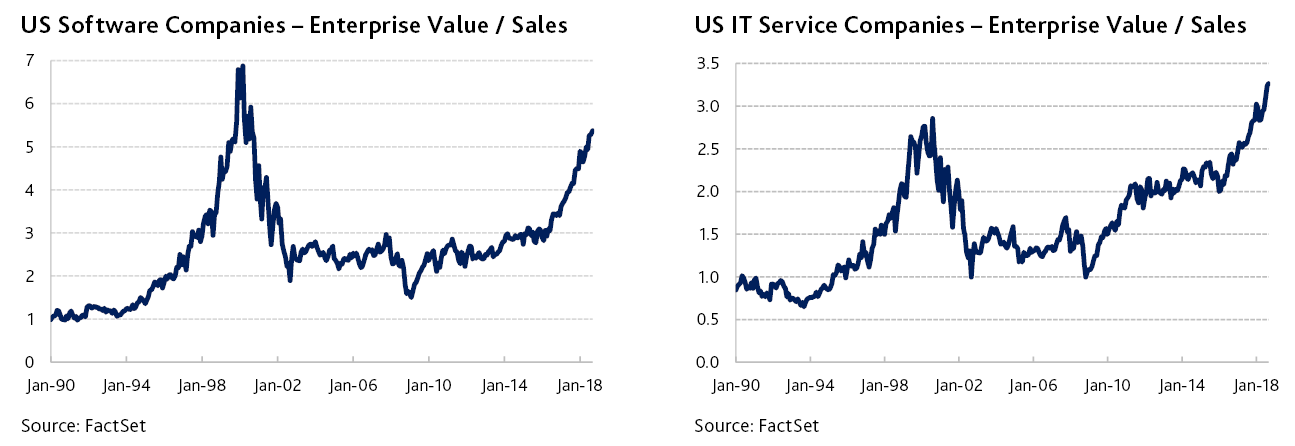

From an investment point of view, it is worth observing that the strong performances in areas such as technology and healthcare have been driven by stocks that, based on our research, were already expensive by historical standards. Software stocks and internet companies that have been central to the strong performance of the technology sector in recent months are now valued against their revenue base at levels only exceeded in the technology bubble of 2000, as illustrated in the following charts.

While the valuation of biotech stocks is not so readily demonstrated by reference to comparable historical data, as Bianca Ogden explains in the Platinum International Health Care Fund Report, valuations are stretched, and the record number of new biotech IPOs[8] is also strong confirmatory evidence. By stark contrast, six months ago, the deepest value was to be found in the North Asian markets of Korea, China and Japan, and yet these markets have performed poorly over the period.

This has led us to conclude that, outside of the favoured growth stocks, markets are pricing in a future that is substantially different from the world that can be observed today. Essentially, cyclical stocks are factoring in a significant slowdown in global growth. While this could be the case, there are a number of reasons suggesting that the picture may not be quite so grim:

-

As outlined above, the scope and impact of the trade measures put in place to date are limited relative to the broader economic backdrop. As such, the trade war would need to ratchet up significantly to further impact on markets.

-

There is an underlying futility to the trade war that needs to be resolved with a face-saving political solution for its proponents. It is instructive that the US has now come to an agreement with Canada and Mexico on trade that achieves little substantive improvement on the existing North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), but represents a political win for the Trump administration. While a resolution will take time and there may be further damage before one is reached, it is not entirely unrealistic to expect a deal with China at some point.

-

Meanwhile, China has moved to stimulatory policies to underwrite growth. As they have done in past, such policies will likely achieve some of their intended effect.

-

While higher interest rates should ultimately slow the US economy, given the existing strength in labour markets and the availability of ongoing fiscal stimulus, a slowdown may well be further out on the horizon.

To sum up, markets are currently positioned in a very defensive manner, and any lessening of the fears that have driven stock prices in recent months could well see them move higher. Of course, there is always the possibility of some new issue arising, especially in a world where balance sheets are weak and interest rates unsustainably low. But for the moment, investors appear to be leaning very heavily in one direction. More often than not, it pays to head in the other direction.

[1] The latest round of tariffs on US$200 billion of Chinese goods are applied at 10%, with the possibility of increasing to 25% in January 2019 if the Chinese don’t accept US demands for various changes.

[2] “Bringing iPhone Assembly to U.S. Would Be a Hollow Victory for Trump” by Greg Ip, The Wall Street Journal, 19 September 2018, citing a study on the value added in smartphones by Jason Dedrick of Syracuse University and Kenneth Kraemer of the University of California at Irvine.

[3] Based on new car registration data between January and December 2017: www.statista.com/statistics/269872/largest-automobile-markets-worldwide-based-on-new-car-registrations/

[4] 24% for GM, 28% for BMW, 30% for Mercedes, 37% for Ford, 49% for Volkswagen Group, and 56% for Audi (based on 2016 China profits before tax as a percentage of global total). Source: Evercore ISI and Financial Times.

[5] Source: US Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Foreign Trade Division; Bureau of the Census USA Trade https://automotiveaftermarket.org/automotive-aftermarket-imports-exports/.

[6] Peer-to-peer (P2P) lenders are intermediaries, typically online platforms, that match people who have money to invest with people who are looking for a loan. Well-known P2P lending companies include Lending Club in the US, RateSetter in the UK, and Society One in Australia. Chinese P2P lending platforms are largely similar to these.

[8] There were 47 biotech IPOs in the first nine months of 2018, already more than both the full years of 2016 and 2017. (Source: Renaissance Capital)

DISCLAIMER: The above information is commentary only (i.e. our general thoughts). It is not intended to be, nor should it be construed as, investment advice. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Before making any investment decision you need to consider (with your financial adviser) your particular investment needs, objectives and circumstances.