More than 800 million Chinese consumers are carrying e-wallets on their phones, and mobile payments made via China’s third-party platforms such as Alipay and Tenpay – some US$5.5 trillion – were 50 times the value of e-payments transacted in the US last year.

Browsing on Weibo, China’s equivalent of Twitter, I was amused by a piece of local news:[1] Two brothers in their twenties went on a rampage in the eastern Chinese city of Hangzhou, robbing three 24/7 convenience stores at knifepoint, but walking away with a meagre RMB 2000 (~US$300) in total, not even enough to cover their travel expenses for getting to Hangzhou! The disappointed thieves reportedly grumbled to police that local residents no longer spent cash. Chinese netizens were quick to respond that the brothers had chosen the wrong target – didn’t they know that Hangzhou is Ma Yun’s turf, and who still carries cash around when there is Alipay!

Ma Yun (aka Jack Ma), as you would know, is the founder of the Hangzhou-headquartered e-commerce giant, Alibaba Group (a holding in the Platinum International Fund and the Platinum Asia Fund), as well as the founder of Ant Financial, the company that owns the ubiquitous e-payment system, Alipay, an affiliate of Alibaba Group.

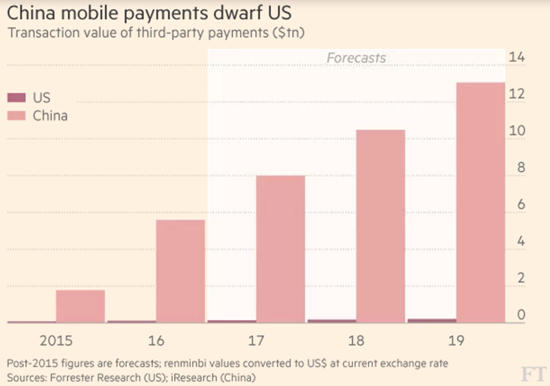

What is remarkable isn’t that the use of non-traditional payment channels is on the rise in China, but the pace and scope at which it is happening, which has largely been propelled by Alipay and Tenpay, the digital payment platform owned by Tencent (another key holding in several of Platinum’s funds). Last year, Chinese consumers made RMB 38 trillion (approximately US$5.5 trillion) worth of payments on their smartphones and tablets using such non-bank operated e-payment services (so-called “third party” mobile payments), a 215% increase from 2015.[2] This was 50 times the transaction value in the US, which saw US$112 billion worth of payments made last year via mobile payment platforms like PayPal, Apple Pay and Google Wallet, according to Forrester Research.

Source: Financial Times, based on data from Forrester Research (US) and iResearch (China).

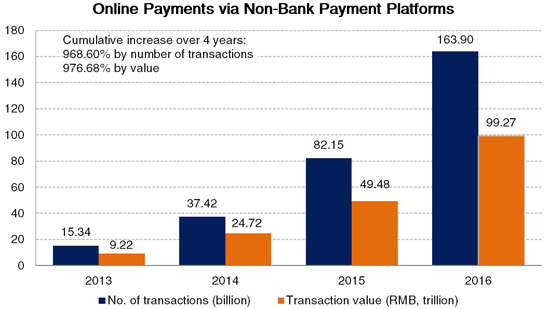

When one looks at online payments more broadly to include all of internet, mobile, telephone and digital TV payments,[3] data from China’s central bank shows that online transaction value via non-bank platforms nearly reached RMB 100 trillion (~US$14 trillion) in 2016, a 970% increase over four years by both transaction volume and value.[4]

Source: People’s Bank of China (PBoC), Payment & Clearing Association of China and Platinum

Driving this phenomenal growth are the innovative tech companies seeking to meet the needs of China’s consumers and small businesses who had long been under-served by the country’s banks.

Alipay was first launched in 2003 as an online payment and escrow system to service Alibaba’s e-commerce marketplace, Taobao, before it rapidly expanded into a standalone platform, facilitating third-party online transactions ranging from travel bookings to phone credit top-ups and utility bill payments. Its origin was not dissimilar to the way in which PayPal was born out of eBay, but its adoption grew more quickly as fewer alternative means of online payment were open to the Chinese consumer. There was no equivalent of BPAY, few possessed a debit card, and even fewer a credit card. To put things in context, by the time Alipay had accumulated 50 million users in 2007, there were only 30 million credit card users in the country with a 1.3 billion population.[5] Today, credit card ownership in China averages 0.31 card per person (2016),[6]compared to 2.6 cards in the US (2014).[7] A public that has grown accustomed to the convenience of credit cards for over half a century in part explains the slower conversion to e-payments in countries like the US and Australia, and, conversely, one imagines the early adoption of e-payment in China may have somewhat handicapped the growth of traditional credit card businesses there.

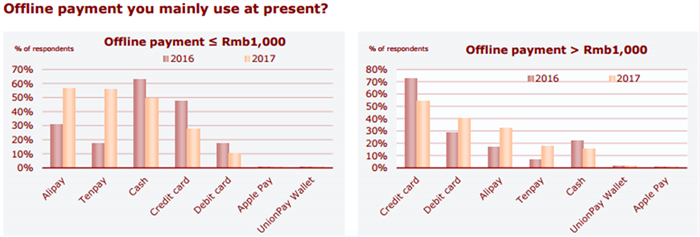

Then came a second great leap. Enabled by the proliferation of affordable smartphones, Alipay and Tenpay began expanding from online to offline in 2013, making mobile payment increasingly the preferred method – or methods – of transacting at physical stores over both cards and cash.

Source: CLSA CRR

Source: CLSA CRR

One of the in-store e-payment methods effectively replaces plastic cards with digital barcodes. After logging onto his, say, Alipay mobile app, which requires a password, a fingerprint or another alternative means of authentication, the customer would generate a unique barcode from his phone at the press of a button. Then all it takes is a simple scan at check-out and the correct amount would be deducted from his Alipay account and paid into the merchant’s account. If that is not convenient enough, an alternative system is available which does away with the scanner and point-of-sale terminal completely, making it particularly suited to street vendors, rideshare drivers and other small merchants. The merchant needs only to display its unique QR code, supplied by the e-payment platform, say, Tenpay. When the customer scans the QR code with her phone, a connection is established between her Tenpay account and the merchant’s. She then enters the payment amount and her password, and the transaction is confirmed. The funds are transferred instantaneously and a notification is sent to the merchant’s phone. There is no need to find the right change, and counterfeit notes are not a worry (of course, cybersecurity and identity fraud may over time emerge as a greater concern). Adding to the sheer simplicity of their service is the attraction of Alipay’s and Tenpay’s service charges, which are typically lower than the traditional merchant fees collected by banks and credit card companies. It is hard to think of a reason why merchants and customers would not forego the cumbersome cash and expensive plastic money for e-payment (unless, of course, you were one for tax evasion at the expense of lost custom).

Source: Bloomberg, iFeng News and Platinum

As China’s third-party mobile payment market grows, the competition is also becoming more intense. Tenpay, first launched in 2005, has had a slow start, as it lacked Alibaba’s e-commerce merchant and customer base and struggled to expand its user base beyond Tencent’s online gaming community. However, growth began to accelerate after Tenpay in 2014 became integrated with WeChat, Tencent’s enormously popular “messaging + social networking + utility + enterprise” omni-functional app. Leveraging off WeChat’s 889 million users and its enormous network effect as the main digital tool the Chinese use to stay in touch with family and friends, Tenpay cleverly built up its consumer base by first promoting peer-to-peer transactions with a virtual rendition of the old tradition of gifting money in red envelopes. As of the fourth quarter last year, Tenpay had 838 million active users, well surpassed Alipay’s 432 million.[8]

With this large user base, Tenpay naturally became increasingly attractive to merchants and businesses, more and more of whom are also using WeChat as a marketing tool – there are now more than 10 million commercial or “official” accounts on WeChat. These businesses are now taking advantage of Tenpay’s integrated payment functionalities within the WeChat ecosystem in both online and offline settings. As Chinese netizens use WeChat to hail taxis and order meals, whether inside a restaurant or online for take-out, they pay the drivers and split restaurant bills using Tenpay; as retailers put out promotional coupons on WeChat, their followers can redeem the coupons by making an in-app purchase or turning up at a brick-and-mortar store and scanning a QR code. It is no wonder that Tenpay’s share of the third-party mobile payment market is increasing fast, reaching 37% in the fourth quarter of 2016, while Alipay continues to command 54% of the market.[9]

With the huge user base and transaction volume come huge amounts of valuable data. As Andrew Clifford mentioned in his account of a recent trip to China, Ant Financial has developed a credit rating business, Sesame Credit, whose data form the basis of the lending criteria for a host of lenders seeking to service small-to-medium sized enterprises and individual borrowers under-served by large banks. In 2013, the same year that Alipay expanded into offline payments, Ant Financial also ventured into offering innovative investment products. It first launched Yuebao (meaning “the treasure of account balance” in Mandarin), a platform that allows customers to use the excess funds in their Alipay accounts to invest in wealth management products with as little as RMB 1 and with the flexibility of withdrawing at any time. The returns offered by Yuebao were often on a par with bank deposit rates or better, making the product very attractive. Today, with more than US$165 billion under management, Yuebao has become the world’s biggest money market fund.[10] Building on the success of Yuebao, Ant Financial has since launched Zhaocaibao, an online distribution platform for financial products ranging from mutual funds and insurance policies to P2P lending, Cunjinbao, a gold ETF, Ant Fortune, a robo-advisory service, and Antsdaq, an equity crowdfunding platform. Alipay, the humble online payment tool, has ushered China into a fintech era.

As I laughed at the Weibo news post about the empty-handed robbers in Hangzhou, a voice message popped up on my WeChat. The message was from my mother, who had just arrived in Beijing to visit family, scolding me for neglecting to install Alipay and Tenpay on her phone. She was unable to make a purchase at the Beijing airport duty-free store as there was nowhere to exchange AUD for RMB. And when she stared in wonderment at her fellow passengers, who were either picking up goods without paying (because they had prepaid for them online) or simply waving their mobile phones about at check-out, she was told “I don’t carry cash any more; I’ve Alipay on my phone”.

DISCLAIMER: The above information is commentary only (i.e. our general thoughts). It is not intended to be, nor should it be construed as, investment advice. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Before making any investment decision you need to consider (with your financial adviser) your particular investment needs, objectives and circumstances. The above material may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Platinum Investment Management Limited.