Global health crisis takes unprecedented personal, economic and market toll

The global economic environment and financial markets were upended in the last few weeks of the quarter as the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic made its way across the globe. The headlines clearly tell the story. As governments sought to contain the spread of the virus, there have been mass closures of businesses, resulting in unheard of jumps in unemployment. Stock markets collapsed in one of the fastest declines in history and debt markets are struggling under the possibility that companies that only weeks ago looked in good financial shape are now bankruptcy candidates.

The Economy

In order to have a view on where economic activity may track from here, we need to address the nature of this economic collapse. We are all used to the economy being defined by sets of numbers such as interest rates, inflation, employment, retail sales, government spending, trade deficits and surpluses and the like. While these are all useful indicators of what has happened, viewing the economy through the lens of such data tends to make us think of the economy in an abstract manner.

The economy is real. People get out of bed everyday and go to work or at least go looking for work. Once at work, we use the computer in an office, the machinery in a factory, or the intellectual property in a research laboratory. In doing our work we have access to natural resources, whether that is simply the land on which the office or factory sits, the ore taken out of the ground at a mine site, or water and soil in agricultural activities. Economists refer to these elements of the economy as labour, capital, and land, and are collectively referred to as the “factors of production”. The goods and services produced using the factors of production are our income and the sum total is referred to as gross domestic product (or GDP). These factors of production and the goods and services produced are the real economy.

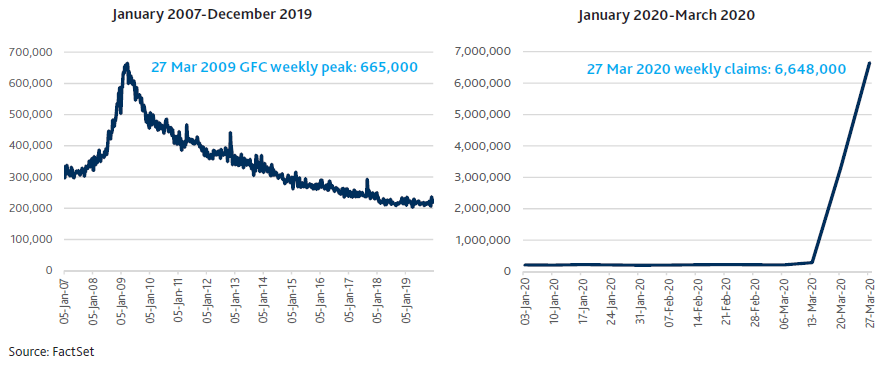

Governments around the world have reacted to COVID-19 with a wide variety of containment measures to slow down the spread of the disease. In nearly every case, the result of these measures has been to limit the ability of people to go to work and spend money (e.g. at bars, restaurants, travelling), thus removing the opportunity for work in these industries. It is this restriction on the economy’s key factor of production, labour, that has resulted in the collapse of activity. Of course, without labour, much of the other factors of production go to waste as well. This collapse is nowhere better demonstrated than in the United States, where initial unemployment claims spiked to 3.3 million in a single week in March (up almost 12-fold from the previous week). They then jumped a further 6.6 million the following week (see Fig. 1), which is almost 10 times the previous record set during the global financial crisis (GFC).

Fig. 1: Rise in Weekly US Jobless Claims Demonstrates Collapse in Economic Activity

Weekly Initial Claims For Unemployment Insurance Under State Programs, Seasonally Adjusted, Persons - United States

The key point to be taken from all of this, is simply that, economic activity will stop falling and start to recover when people can return to work. Exactly when containment strategies can be wound back is unknown at this stage. There is much attention on China as a roadmap and recently Wuhan (the epicentre of the outbreak) has started to re-open a little over two months after the initial lockdown of the city. There is considerable uncertainty about whether this timeframe will be representative for the rest of the world and indeed, what will happen in Wuhan as freedom of movement returns. However, at this point in time, the data from the rest of China suggests reasons to be optimistic that we will be able to slowly get back to work once the spread of the virus has been controlled.

Once we can all get back to work, the productive capacity of the economy, as represented by the factors of production, will be largely undiminished and in theory, economic activity should quickly regain much of what has been lost. In practical terms though, many businesses that have been closed may never return, simply because they were marginal in the first instance, or as a result of bankruptcy. While the closure of these businesses will release resources that can be used in other activity, this takes time.

How quickly will activity return to prior levels? Looking to history, probably the most appropriate period for comparison is the GFC. During the GFC, the breakdown in the financial system saw business activity stifled due to a lack of funding, and similarly to today, resulted in a period of time where the productive capacity of economies could not be put to use.

There was also a dramatic fall in activity, though not as rapid as we have experienced in recent weeks. After the major economies peaked in early 2008, it took the US economy just over three years to return to this level, Japan took five years, and Europe took seven years. Of course, this crisis has a different cause, and we still do not have a clear sense of the depth or length of the economic decline. All that can be stated with any confidence really, is that while the rebuilding will start the day we get back to work, it will take some time before we can recover to the previous highs in economic activity.

There is also the issue of government responses to the crisis. These vary significantly across countries, but generally the various fiscal and monetary policies that have been enacted can be grouped into two categories. Many countries have created lending facilities for companies that are struggling to finance their ongoing operations. Typically, the central bank is either directly offering funds to businesses, or indirectly via the banking system, often at concessional interest rates.

These policies are aimed at ensuring companies do not fail as a result of not being able to access funds due to the short- term freeze in debt markets and banks trying to protect their positions. The goal of governments is to ensure people have jobs to go back to when we are through this period of containment. There has also been large-scale buying of financial instruments by central banks, which has played a similar role in ensuring that financial markets continue to remain open and able to provide funding to companies. The second key area of focus has been the provision of funding to individuals who have lost their jobs or have been temporarily laid off. The large percentage of workers who have lost employment are from relatively low-income roles in the tourism, retail, and other service industries, and typically have little room within their finances to sustain themselves through a period of unemployment. Payments to those impacted will ensure they can afford their weekly grocery bill and await the chance to search for work at a later point in time.

What is important to understand about these policies is that they achieve very little in the way of new activity. Simply, going back to first principles, if people can’t work for whatever reason, economic activity will remain suppressed. It helps that a newly unemployed individual can afford the weekly grocery bill, but in the scheme of the broader loss of activity, this is marginal. The various policies ultimately aim to remove the worst-case outcomes from the economic collapse and they effectively do this by redistributing the burden of the crisis from those who are initially impacted (such as those who lose their jobs), across the broader community. While governments can spend money, they are not a source of economic activity. When they spend, they do this either by raising funds through taxation, borrowing money from the private sector (which then has to be paid for from future taxation receipts) or by printing money. The burden of today’s spending measures by governments will either be funded from taxation (today or in the future) or through a loss of value in money or cash (i.e. inflation). It is not to say that these policies are not necessary. It is just to state that these are the mechanisms by which the burden is spread more broadly across all in society.

Once we do come out the other side of this crisis, it is likely that consumer and business confidence will recover slowly, especially in the light of the damage to household and corporate balance sheets. Additional government spending is likely to remain a feature of the environment, as governments attempt to fill the spending gap left by the private sector. At this point, such spending will aid in creating economic activity as it helps create employment. The future economy may potentially look quite different, as some industries may simply not recover and the growth path of others, such as e-commerce, information technology, renewal energy and healthcare, will be reinforced by today’s events. Government spending on infrastructure, not just on the typical ‘roads and bridges’, but healthcare and efforts to decarbonise economies, seem likely. There will potentially be interesting challenges around the future funding of government initiatives given the deterioration in national balance sheets resulting from current policy initiatives.

In Summary:

- The current economic shock is a result of large numbers of people being unable to work as a result of the strategies to contain COVID-19. There can be no economic recovery until people can get back to work.

- Current government initiatives around the world will prevent worst-case economic outcomes and help share the costs of the downturn across society. Government policies will have little impact in creating activity until we start to move beyond containment strategies.

- Ultimately, a recovery in the economy will take hold, though it will take time to recover to 2019 levels and this may vary dramatically by country. Further, the make-up of our economies may be very different in the recovery period, compared with that of 2019.

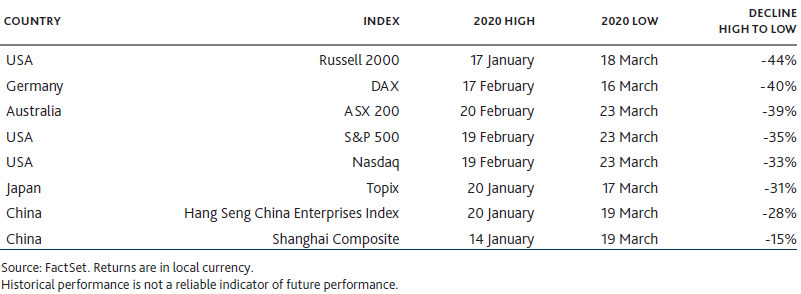

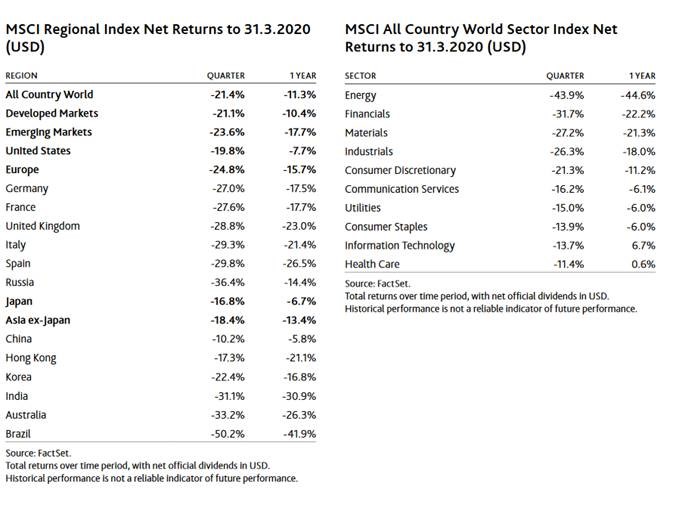

The response of stock markets to the unfolding pandemic has been swift, recording some of the largest and fastest declines on record. From peak levels in markets during the first weeks of 2020 to their lows in the second half of March, markets fell between 31% to 44% in local currency terms (see Fig. 2). The exception was China, which had already been in a protracted bear market for some time.

Fig. 2: Market Declines from 2020 Highs to Lows

These are very significant adjustments by any standards, other than against the most significant bear markets in history. For reference, during the GFC the S&P 500 Index fell 57% from its peak in 2007 to its trough in early 2009, Germany fell 54%, Japan 61% and Australia 54%.1 The comparison with the GFC is interesting, as the decline in economic activity in the current downturn has been far swifter. However, if the rest of the world follows the experience of Wuhan and is able to release the lockdowns after two to three months, the base in economic activity is likely to be reached relatively quickly.

As discussed above, the recovery in economic activity will begin when people can go back to work, though a full recovery will take time. However, markets will anticipate the full recovery well ahead of its actual occurrence. Post the GFC, stock markets rallied strongly in subsequent years, well ahead of the full economic recovery. Ultimately, the market is likely to reach its low at the point of greatest uncertainty. Potentially, we have already seen that occur as the major monetary and fiscal initiatives that were announced by governments at the end of March did reduce some of the worst-case scenarios as discussed earlier. On the other hand, there were rallies in markets of the order of 20% on two occasions in the latter months of 2008, only for the market to falter and fall to new lows.

There remain many unanswered questions at this point. Besides the length of the lockdowns occurring around the world, the quantum of the economic loss is far from clear. Additionally, the impact of the slowdown on company profits is not linear. Companies with high fixed overheads will incur significant losses and will need to either take on debt or issue equity to survive. Others may find profits suppressed for a number of years if revenues remain subdued. Probably of greatest concern is what appears to be a highly disorganised response in the US, the world’s largest economy.

Our view at the time of writing, is that markets will likely return to their recent lows and possibly fall further. It is likely that this will occur relatively quickly as many of the uncertainties outlined above will start to be better understood with each passing day. Our position may change quickly. Ultimately, what will guide our longer-term position is the value that we can see in current stock prices. We do this by taking a view on the earnings power of companies three to five years in the future, based on our assessment of their business prospects. We will adjust valuations for losses that we expect them to accrue during the worst of the downturn. We will assume a reasonable rebound in future economic activity in aggregate, but will not expect this to play out evenly across all industries. On this front, we have a mixed view. There are many extremely attractively priced companies, particularly in cyclical areas and those areas directly impacted, such as travel. On the other hand, many market darlings of recent years, while having been sold off, have continued to perform better than the broad market and remain expensive.

[1] All index and market returns in this Macro Overview are in local currency terms and sourced from FactSet unless otherwise specified.

DISCLAIMER: This information has been prepared by Platinum Investment Management Limited ABN 25 063 565 006 AFSL 221935, trading as Platinum Asset Management ("Platinum"). It is general information only and has not been prepared taking into account any particular investor’s investment objectives, financial situation or needs, and should not be used as the basis for making an investment decision. You should obtain professional advice prior to making any investment decision. The market commentary reflects Platinum’s views and beliefs at the time of preparation, which are subject to change without notice. No representations or warranties are made by Platinum as to their accuracy or reliability. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted by Platinum or any other company in the Platinum Group®, including any of their directors, officers or employees, for any loss or damage arising as a result of any reliance on this information.

Disclaimer

DISCLAIMER: The above information is commentary only (i.e. our general thoughts). It is not intended to be, nor should it be construed as, investment advice. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Before making any investment decision you need to consider (with your financial adviser) your particular investment needs, objectives and circumstances.