In our March 2017 quarterly macro overview, Andrew Clifford, CIO, recounted the causes and effects of the current imbalances in major global economies, including some of the investment implications the trade imbalance and an impending rebalancing hold for China in particular. This article builds on Andrew’s framework and explores what these phenomena mean for investors in Europe.

Investors are wary of Europe. Understandably so. Their perceptions of the region have been shaped by recent experience, particularly the Sovereign Debt Crisis of 2012-13. When investors think of Europe, they are haunted by memories of the economic weakness and instability, the bickering policymakers incapable of decisive action and the political upheaval that defined this period. At present, investors assign an extremely high premium to safety and predictability. So the instability and uncertainty they associate with Europe repels them.

But, here lies a fundamental misunderstanding.

To illustrate, consider the following thought experiment. Imagine an individual who lives a lavish lifestyle. To do this, he spends a lot more than he earns. And he does this year after year for many years. Today, he owes a mountain of debt. Now suppose the economy takes a nasty turn, becoming less stable and more uncertain, but at the same time, interest rates collapse.

What would you do if you were in their shoes? Would you take advantage of low interest rates to borrow even more and spend harder? Or would you use the breathing space afforded by low interest rates to repay some debt and bring your affairs to order?

Many countries around the world were in precisely this position in 2009. Most took the advice of 'economic experts'. They borrowed more and spent harder. But if this doesn’t make sense for an individual, then it doesn’t make sense for a country. The arithmetic is the same.

Europe is interesting because Europeans made a different choice. They chose to get their financial house in order.

‘Choice’ is an exaggeration. Citizens of democracies don’t volunteer to reduce their standards of living. Circumstances force adjustments upon them. Many stomped off to fiscal rehab only after an acrimonious process of negotiation, horse-trading, name-calling and brinkmanship. This unseemly drama played out in full view of the world; nothing is private in the Internet age. While eye-catching and highly memorable, the processes of how they got there is utterly irrelevant. Only one thing matters. Deficit nations bit the bullet. They began tightening their belts, repairing their balance sheets and reforming their economies.

|

Europe's Current Account Transformation |

||

|

|

Current account to GDP 2008 |

Current account to GDP 2016 |

|

Greece |

-11% |

0% |

|

Portugal |

-10% |

+1% |

|

Ireland |

-6% |

+12% |

|

Spain |

-4% |

+2% |

|

Italy |

-3% |

+3% |

|

Germany |

+4% |

+8% |

|

Source: Bloomberg |

||

The price of rehabilitation was the recession Europe experienced in 2012-13. This is talked about a lot. The benefits barely rate a mention. In 2007, many Eurozone members ran substantial current account deficits. Today, practically none does. What this means is that Europeans today are:

- living within their means;

- repaying their debt; and

- competing effectively in the global economy.

This matters. These changes have made European economies much more resilient and less vulnerable to economic shocks than they were in the past. And that’s simply not true for those countries that chose more debt and more spending, including the United States, Great Britain and Australia.

To condemn the Europeans for the economic weakness and policy paralysis that we observed during the Sovereign Debt Crisis is to miss the point entirely. This was a period of profound change that set Europe up really well for the future.

That future is now here. Europe is growing once again. The recovery is robust. It is spreading across countries and sectors of the economy. Unemployment is falling. Economic growth is accelerating. Europe grew faster than the United States in 2016, and it is at a much earlier stage of its recovery, so this economic revival has room to run.

Corporate earnings in Europe are depressed, reflecting the region’s weak economic performance since 2009. The United States, by way of contrast, is now in its eighth year of economic recovery. Corporate earnings there have grown steadily and have now comfortably surpassed their 2007 peak. As the European economy gathers momentum, it’s not unreasonable to think European corporate earnings will follow a progression similar to what has been observed in the United States.

This is not reflected in stock prices. European stocks trade on lower multiples of earnings than their American counterparts, on average. This is the case despite the fact that earnings in Europe are severely depressed by comparison. Simply put, when you buy European stocks you receive more and pay less. You get this because Europe is unloved and misunderstood.

At Platinum we invest in businesses, not continents, regions or countries. However, having a framework for understanding global financial imbalances, along with how and why they persist, helps us understand how Europe is misunderstood and why this gives rise to investment opportunities. This framework is not the basis for our investment decisions, but we use it to guide our search for under-appreciated businesses. Rather than sifting through hundreds of companies at random, we can target our search, knowing much more systematically where to look.

In the European context, one of the places this framework has guided us to is Germany. Not to the export champions that the market knows and loves. But to the domestic economy: German companies that serve German consumers and the German property market.

So why do Germany’s current account surpluses make the country’s domestic economy a bountiful source of investment ideas? While highly technical, it’s actually also quite intuitive.

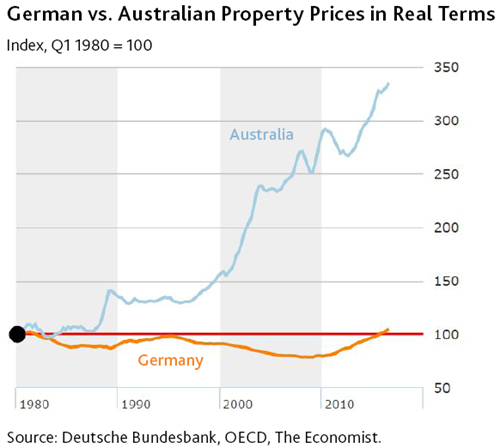

Consider for a moment our own experience, as Australians, participating in this economy over the last thirty-odd years:

-

We have enjoyed a period of unprecedented economic stability. We have not experienced a recession in 26 years. This is now officially a world record.

-

During this time unemployment has been relatively low. Employers consistently complain of the difficulty of finding suitably skilled workers and lobby for more skilled migration. Our job security is high. Our prospects of finding employment are good.

-

Reflecting this, wages have grown faster than inflation with Australian incomes now very high by international standards.

-

House prices have appreciated phenomenally over this period. We have generated more wealth through capital gains on property than we ever could have by working and saving.

This experience has conditioned us to be confident about the future. We are confident enough to spend more than we earn. We are confident enough to take on a lot of debt. We are confident enough not to feel the need for precautionary savings. We feel wealthy.

This experience is what a current account deficit economy feels like.

Now try and imagine the world through German eyes over the same thirty-year period:

-

They endured not one but four recessions; one every seven years on average and two in the last decade alone.

-

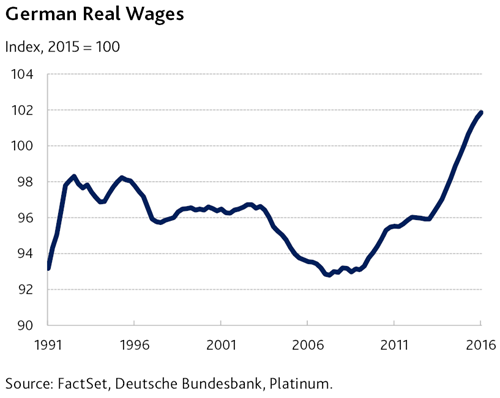

In 1990, 16 million East Germans joined their economy. Businesses were spoilt for choice, but for workers it meant two decades of high unemployment, low job security and poor prospects of finding employment.

-

Reflecting this, inflation-adjusted wages did not increase at all between 1990 and 2010. That’s twenty years without a pay increase.

-

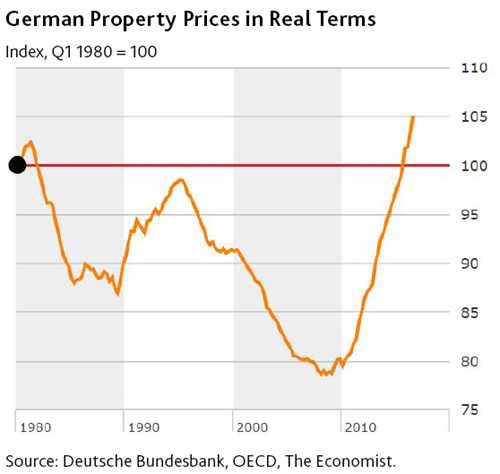

Many Germans own their homes, but inflation-adjusted house prices went sideways from 1980 to 2010. That’s thirty years with no capital gain to speak of.

This experience has conditioned Germans to be cautious. They are miserly with their spending. They eschew debt. They hold significant precautionary savings. They invest their savings in bank deposits, not property and shares. Make no mistake, Germans are well off. But they got there the old-fashioned way. Slowly! By working and saving.

This experience reflects what a current account surplus economy feels like.

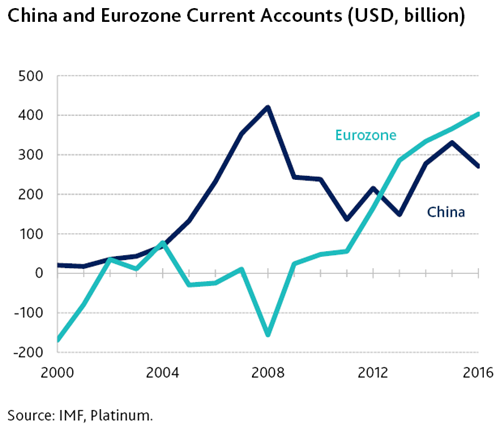

For over three decades, countries like Japan, China and Germany have generated large surpluses of savings. These were channelled by capital markets to deficit countries where they enabled households, businesses and governments to gear their balance sheets. This fuelled asset price booms in deficit countries and allowed households to live better and spend more than their own incomes would allow.

This is the world as we have known it for three decades. But it’s changing.

China’s provision of surplus savings to global capital markets has reduced significantly since 2010. Rising incomes and growing confidence have seen Chinese consumers opt to spend more on homes, cars, travel and consumer goods. They are spending more of their income and sending less of it overseas to be consumed by foreigners.

Surprisingly, this has so far done little to disrupt the status quo. And that’s because Europe, in particular, has picked up the slack. In the act of getting their finances under control in 2012-13, peripheral European countries reduced an important source of demand for surplus savings and added to their supply. Meanwhile, the weak Euro has meant that Germany, a leading global supplier of surplus savings, is now producing more than ever.

But Germany is becoming a less reliable source of surplus savings. Two factors in particular are driving this change.

First, wages are rising. The German economy has been strong for so long that the labour market, for many years oversupplied, is now tight. Unemployment, which averaged 9% for two decades now sits at 4%. Wages, having been flat for twenty years, have increased 20% since 2010.

Second, interest rates are too low. The European Central Bank has set interest rates at -0.4% to support the likes of Greece and Italy. This is not appropriate for Germany where the economy is booming. The effect is rising house prices. Having gone sideways for thirty years, German house prices have appreciated by more than 30% in real terms since 2010.

When it comes to global financial imbalances, Germany and Australia sit at opposite ends of the spectrum. As Australians, we know the types of businesses that thrived in the environment we’ve experienced: banks, property developers, mortgage brokers, estate agents and various retailers. In Germany, we own a range of such companies, including:

- ING Group, the second largest retail bank in Germany by deposits.

- Hypoport, a leading mortgage broker and facilitator.

- Scout24, the most visited German online property classified.

- Hornbach, a leading German hardware retailer.

As incomes and house prices rise, Germany is becoming a bit more ‘Australian’ and these sorts of businesses will do better. Yet, the market isn’t pricing this in. These businesses have boring track records because the German domestic economy has been deprived of oxygen for so long. As a consequence, they are overlooked by investors.

Investors focus on what was or what is, because that’s knowable. It’s easy. Yet, what really matters is what will be. Ascertaining that is hard. This is why it is crucial to have a framework to help us understand why the world is the way it is and how and why it is changing. Having such a framework allows us to invest looking to the future rather than to the past.

The future is by no means certain. These global financial imbalances will correct themselves, but the process may be slow and far from linear. We can’t know how it will play out. But we don’t need to. All we need to do is ask some simple questions:

-

Would one rather own businesses that serve highly indebted consumers dependent on the savings of foreigners to maintain their level of spending? Or businesses that serve consumers with little debt, high levels of savings and rising incomes, and ones that have deferred consumption for many years?

-

Would one rather own businesses that serve property markets where the incremental buyer has no savings and is geared to the hilt, and where property prices have already appreciated multi-fold? Or businesses that serve property markets where the incremental buyer has large pools of cash earning zero per cent in their bank account, little debt and rising incomes, and where prices have barely moved in thirty years?

The answer seems obvious enough. Yet, most global fund managers – of both active and index funds – have half of their portfolios invested in the United States and Great Britain, two economies that sit astride the very same economic fault line as Australia. This would seem particularly concerning for the average Australian investors who have their income and most of their assets dependent on the health of the Australian economy.

The Platinum International Fund by contrast has around 70% of its capital invested in Asia and Europe, predominantly in countries that generate excess savings. From Andrew’s coverage in last quarter’s report, it should be clear why Asia, particularly China, has presented us with an abundance of promising investments. And from this paper, it should be clear why Europe, for all the misunderstanding and negative sentiments it has engendered, is serving up no shortage of attractive ideas.

DISCLAIMER: The above information is commentary only (i.e. our general thoughts). It is not intended to be, nor should it be construed as, investment advice. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information. Before making any investment decision you need to consider (with your financial adviser) your particular investment needs, objectives and circumstances. The above material may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of Platinum Investment Management Limited.