Interest rates – a tailwind or headwind for equities in 2020?

In our September quarterly update we discussed the strong consensus that had developed among investors and commentators that interest rates would remain at low levels for some time to come, or as it has become known as, the “lower for longer” view. Whenever such strong agreement is present amongst investors it is important to consider the alternative view.

Employment in the major economies suggests otherwise. Over the last five years, the US economy has added 9.8 million jobs, representing a 7% increase in the workforce over that period. Similarly, Europe has added 8.7 million jobs, an increase of 6%, and Japan, with a declining working age population, has added over 1 million jobs, an increase of 2%. While employment is a lagging indicator of economic activity in the short term, these numbers suggest we have experienced a period of relatively robust global growth - one that is not consistent with such low interest rates.

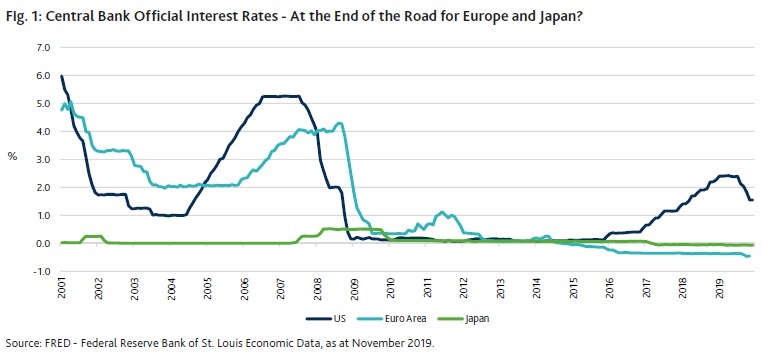

Many investors may observe that interest rates have been low for much of the last 30 years, reaching new lows each cycle, irrespective of the severity of the downturn. The answer then, is simply that interest rates do not reflect the level of economic activity, but rather the interest rate policies of the world’s central banks. With official interest rates below zero in Japan and Europe (see Fig. 1), the limitations of such policies are coming to the fore. The central banks cannot simply continue to reduce rates to ever-more negative levels as depositors, where feasible, will seek to leave the banking system, potentially threatening its viability.

With central banks either close to, or having reached, the end of the road on lower interest rates, it is interesting to note that central banks around the world are calling for an increase in government spending and fiscal deficits to support economic activity. The European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan and Reserve Bank of Australia all made calls in late 2019 for their respective governments to increase fiscal stimulus.

The effectiveness of low and negative rates in encouraging economic activity and the potential side effects, such as increasing indebtedness, is also under discussion. In December, Sweden’s central bank, Riksbank increased its repo rate from -0.25% to 0%, in spite of a slowing economy, quoting concerns about the “negative effects” that may arise from long periods of negative rates. It would not surprise us to see further discussion around the effectiveness of very low interest rates, with central banks ultimately looking for a way out of the corner they have painted themselves into. The immediate issue facing the central banks, as they try to normalise rates, is the level of indebtedness in their economies that these policies have encouraged. It is interesting to note, that such a strong consensus on “lower for longer” has developed at a time when central banks are signalling that current interest rate policies may have run their course.

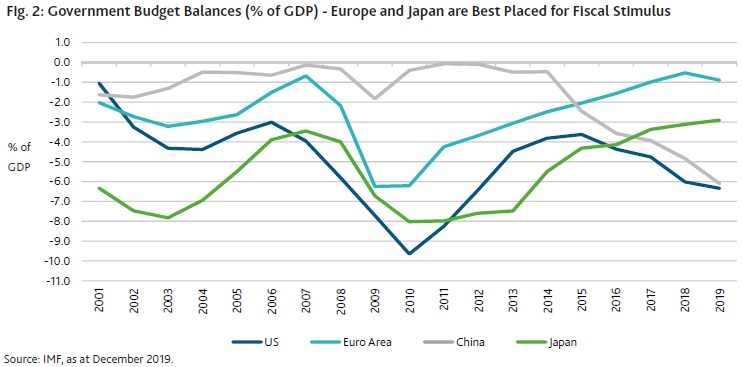

While any move toward normalising interest rate structures may be a long way off, other factors may lead to a pick up in activity in 2020 and beyond, leading to an uptick in inflationary pressures and interest rates. With encouragement from central banks to increase spending and deficits, it is hard to imagine that governments will not follow this recommendation. The US has already undertaken significant fiscal expansion as a result of the 2018 tax cuts, with its deficit currently running at around 6% of GDP (see Fig. 2). Nevertheless, given that the markets are happy (for the moment) to finance this debt at interest rates of less than 2% p.a., and with concerns around the impact of the trade war and an election year underway, an additional round of stimulus is conceivable. China’s fiscal deficit has also increased substantially (currently estimated at 6% of GDP) due to tax cuts and spending initiatives over the last 18 months. Given the Chinese government’s stated desire to restrain the growth of debt across the economy, policy makers are probably somewhat constrained on additional fiscal measures.

This leaves Europe, where the fiscal deficit is around 1% of GDP, and Japan where the fiscal deficit has fallen to 3% of GDP, as the most likely sources of significant additional fiscal stimulus. As discussed last quarter, France and the Netherlands have announced tax cuts, and during the December quarter, Japan passed a supplementary budget of 13.2 trillion yen (or 2% of GDP). Today, Europe and Japan run the world’s largest current account surpluses in absolute dollar terms, which means these economies are significant sources of funding for activity across the rest of the world. If fiscal stimulus results in European and Japanese excess savings being applied within their own economies in any significant way, it is likely to result in greater competition for financial resources across the globe, resulting in upward pressure on long-term interest rates. In addition to the competition for financial resources, any stimulus will come at a time when labour markets in the major economies are relatively tight, which could create some degree of wage inflation, and a further source of upward pressure on interest rates.

Finally, the December quarter saw the promise of a ‘phase one’ trade deal between the US and China[1]. Based on events of the last 18 months, even though the deal is signed, we shouldn’t expect that the trade issue will be set aside completely. Nevertheless, it represents a clear retreat by the US administration from its most extreme positions on trade.

The UK general election result reduces the uncertainty in both the UK and European economies, with the UK exiting the European Union in a more orderly fashion. Both of these outcomes should result in an improvement in business confidence globally.

While the consensus remains that interest rates are not going to rise anytime soon, it is not inconceivable that the economic environment improves over the course of 2020, as a result of fiscal stimulus and less uncertainty around issues such as trade and Brexit. Indeed, we would not be surprised to see rates moving higher over the next 18 to 24 months, back to levels seen at the end of 2018, when US treasuries peaked at above 3%. Certainly problems remain that may derail such an outcome. Most notably the US election process has the potential to create significant noise and uncertainty. Additionally, domestic political protests such as those in Hong Kong and elsewhere, look difficult to resolve, and could potentially escalate further.

Nevertheless, our suggestion is that rates may return to where they were a little over 12 months ago. At that time, the world did not look so different to today.

Market Outlook

While a discussion of interest rates rarely makes for exciting reading, it is currently the critical issue for investors in all asset classes. There are three ways that interest rates are impacting markets today, the first two are perennial features of markets, and the third is peculiar to current circumstances.

The most obvious of these, is the role interest rates play in the valuation of assets. The value of any given asset is a function of the future cashflows that it will produce and the appropriate risk-adjusted interest rate[2]. This is true for all assets, whether it is a listed company, rental property, toll road, or government bond. In theory, the lower interest rates are, the higher the value that should be ascribed to an asset for a given set of expected future cashflows. The impact of ever-falling interest rates has been a significant tailwind for the performance of all asset classes globally for over 30 years. This is a phenomenon we have all experienced, not only in our investment portfolios, but also in the prices of residential property in most markets. While there may be questions of the efficacy of low rates on economic growth, there can be no question regarding the impact of low interest rates on the performance of asset markets. Of course, the role of interest rates in the price of assets is one of the most basic concepts in finance, but worth remembering at this time because as rates reach their bottom, we lose this tailwind and it potentially becomes a headwind. While some postulate that if rates stay low, valuations will continue to head higher, the experience in Japan where rates have been below 2% for 20 years, was that the average valuation of the market halved.

The second impact of low rates occurs in the real world, where the hurdle rate for real investment is lowered. Today, this is most readily observed in the willingness of investors to fund new projects in e-commerce, software, biotech, and other high growth areas, where poor short-term returns on investment are accepted for the potential of a significant long-term pay-off. However, in many cases the amount of capital invested in an area will drive down the attractive return investors are after in the first place. Uber’s ride-sharing business is an interesting example where a company, despite achieving a leading position in a new e-commerce field, faces the continual rise of new entrants, which we would simply put down to the generous funding these competitors have already received. Only once these funds have been lost, or access to them removed, will rationality prevail. A similar experience has occurred for investors in the US shale oil sector, where plentiful capital has ultimately led to very poor returns and consequently companies are now struggling to receive debt or equity funding for such ventures. The low cost of money will see funds attracted by the most exciting opportunity of the moment, ultimately driving down returns. Simply, the availability of cheap money actually changes the future cashflow of the industry, and thus the valuation. This premise fits neatly with our approach of avoiding the crowd, as any sector or business idea that is attracting significant capital today, is likely to have a difficult future.

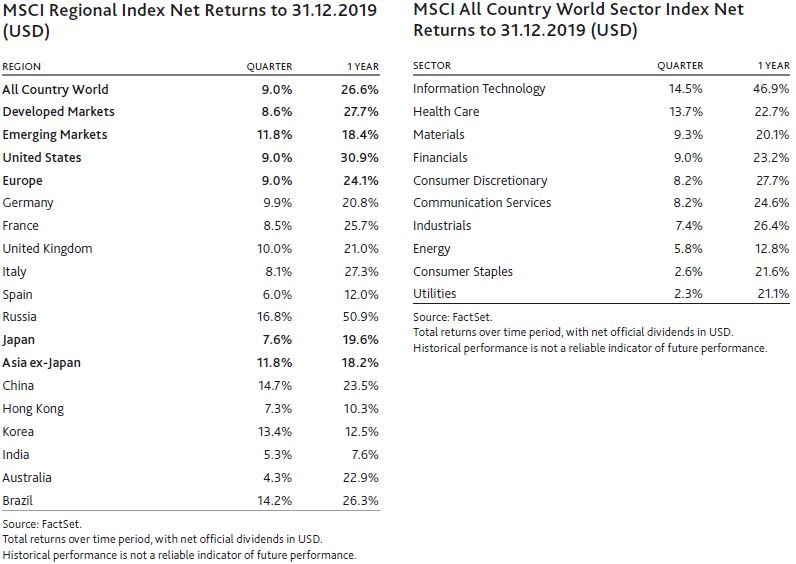

The third impact of low interest rates has been to push investors to seek returns elsewhere, including the stock market. As we have previously discussed, this occurred at a time when there were many reasons to discourage investors from the market, from the global political environment to the disruption of traditional business models. As a result, investors in entering the market have sought either defensive names (i.e. consumer staples, infrastructure, utilities, and property) or high growth areas (i.e. e-commerce, software, payments, and biotech) that are regarded as relatively immune to these issues. Investors simultaneously avoided businesses facing uncertainty (i.e. cyclicals), and in particular those impacted by the trade war (i.e. China generally, automobiles, and electronics). This has resulted in a significant divergence in valuations, with the growth and defensive stocks trading at high levels and the rest of the market trading at generally more attractive valuations. A move to higher interest rates will be particularly challenging for these highly valued sectors.

On the back of optimism around the US-China trade negotiations and the UK general election, markets have entered 2020 on an enthusiastic note. This may continue for some time, but if it is the presage of better economic times, it is hard to see how long-term interest rates can remain suppressed. Given how important the higher-valued defensive and growth stocks have been in driving index levels, a period of softer returns is likely ahead in the broad market.

[1]The US and China announced details of a ‘phase one’ trade deal on 13 December 2019. The US agreed not to proceed with the new tariffs that were due to commence on 15 December 2019 and to also cut existing tariffs on ~US$120 billion in Chinese goods to 7.5% (from 15%) after 30 days of signing the deal. The US’s 25% tariffs on ~$US250 billion on Chinese goods will remain. In exchange, China agreed to buy ~US$200 billion in US products over two years, including US$40-50 billion in agricultural goods. The deal also included Chinese concessions on intellectual property (IP) protections and forced tech transfers, and currency and financial-services provisions. Source: FactSet

[2] Usually referred to as the discount rate in finance.

DISCLAIMER: This information has been prepared by Platinum Investment Management Limited ABN 25 063 565 006 AFSL 221935, trading as Platinum Asset Management ("Platinum"). It is general information only and has not been prepared taking into account any particular investor’s investment objectives, financial situation or needs, and should not be used as the basis for making an investment decision. You should obtain professional advice prior to making any investment decision. The market commentary reflects Platinum’s views and beliefs at the time of preparation, which are subject to change without notice. No representations or warranties are made by Platinum as to their accuracy or reliability. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted by Platinum or any other company in the Platinum Group®, including any of their directors, officers or employees, for any loss or damage arising as a result of any reliance on this information.