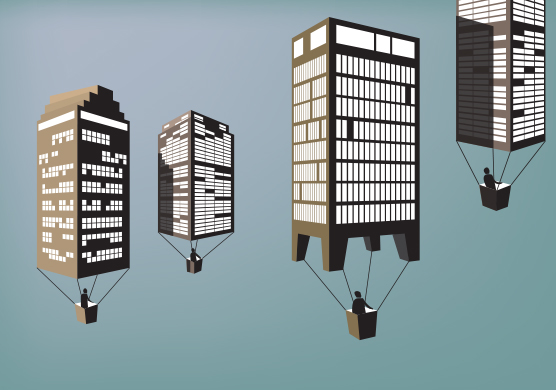

The promise of the new is always exciting, whether it is Tesla taking on the motor industry or cryptocurrencies challenging the fiat money printed by central banks. However, an object lesson for investors in the thrill of the new is banks’ resilience to the onslaught from fintech companies.

In 1994 Bill Gates predicted technology would transform even the stodgy old banking sector when he stated, “Banking is necessary, banks are not.” Back then when the great information superhighway was emerging, such bold visions held immense intuitive appeal for investors.

Yet even after three decades of technological disruption as well as a battering by financial crises, nationalizations and regulators, the market value of the world’s banks is still more than twenty times that of all fintechs. While there have been a few standout fintech successes like PayPal, they are the exceptions rather than the rule and most of them are in Asia.

As a result, Bill’s prediction was more or less forgotten until the recent frenzy around fintech and developments such as artificial intelligence, big data and blockchain. Reading the financial press, one could be forgiven for thinking that fintechs are about to do worse things to banks than Amazon has done to bricks-and-mortar retailers.

However, when investors peek behind the hype they are likely to find reality is more nuanced. Fintechs have struggled to capture banks’ prime customers because the moats of regulation, relationships, data and balance sheets run deep in financial services.

In particular, banks’ size and low cost deposit franchises mean that fintechs cannot compete with the low rates banks are able to offer to prime borrowers. So it is no surprise that few fintech ventures have been launched in the highly competitive mortgage business or in the provision of personal loans to customers with high credit scores. This is where banks offer the best rates and already own and know the customer.

Knowing the customer is critical to assessing loan risks. Banks have much more customer data than fintechs and what they have is more useful than numbers of Facebook ‘Likes’ and Instagram followers. Banks have holistic views of everything from customers’ sources of income to their daily spending. This helps them to cross-sell financial products and, most importantly, to minimize bad debts.

Bad debts are the biggest variable cost in banking across the cycle and this helps to explain why disruption in financial services works differently to other industries. In industries like travel reservations, disruptors like Booking.com and Expedia have succeeded by moving fast to engineer products with lower costs which traditional players find hard to compete with. However, the start-up mantra of ‘let’s move fast and break things’ is dangerous in banking because it tends to result in high bad debts. As a result, risk managers and regulators put the brakes on, giving the incumbent banks more time to respond.

Finally, the ‘relationship hassle factor’ is a wide moat in financial services. Banks’ customers are notoriously loath to switch provider however woeful the service they are getting. This apathy is doubly challenging for fintechs as most of them only sell one or two products. Customers typically do not want a different provider relationship for every product as it is a nuisance. Instead they want the convenience of having all of their accounts in one place. For example, this is why 85% of Australian SMEs hold all of their business products and most of their owners’ personal ones with the same bank.

This makes customers very tactical in how they use fintechs. Most of them only use fintechs for special case risky loans for which the banks have already turned them down. As a result, most fintechs have either partnered with banks or been restricted to niches which banks service poorly or elect not to target.

For example, it is likely the new phenomena of Zipmoney and Afterpay in Australia mostly just extend unsecured debt to youngsters. This is a niche the banks are wary of lending to, though Westpac took a $40mn stake in Zipmoney in 2017. Similarly, in Europe Revolt offers cross-border multi-currency cards where banks have hidden fees and frictions in on-boarding customers.

Asia is where most of the fintechs that are not restricted to small niches or bank partnerships are to be found. In these markets, fintechs were given growth windows in the early stages of their development due to weaker regulation and banks’ focus elsewhere. In addition, most of the major success stories used massive non-financial businesses to slingshot the growth of their fintechs.

Alibaba’s Ant Financial is a case in point with its likely market value exceeding $150bn. When online payment portal Alipay was launched in 2004, there was space to grow because neither China’s (then) uncoordinated mish-mash of regulators nor its banks were focused on consumers and SMEs. Alibaba took its break and leveraged the economic might of its e-commerce business to create a financial behemoth. AntFinancial is now big and powerful, and thus able to compete with the banks.

So despite the promise of the new, upon closer examination it would appear fintechs are not so much gobbling up banks’ customers as nibbling at them. Some have been successful at solving specific needs and in certain niches. However, most have been unable to take over banks’ prime relationships or market shares so easily.

The promise of the new is always exciting, but industry structure, consumer habit and regulation are important and can often work in favor of the incumbents. Exciting thematics are never a substitute for understanding the complexity of the businesses one invests in. Decades of banking resilience and the finer points of the interplay between fintechs and incumbents demonstrate this, no matter how compelling Bill’s prediction seemed all of those years ago.

Understanding this is one reason we have confidence in the significant investments we have made for our clients in banks in Eastern Europe, Thailand, India, Korea, Japan and China. We find the best time to buy banks is typically during a crisis or dislocation. For example, the early 1990s, after Australia’s credit bubble popped in 1989, proved to be an opportune time to invest in its banks while selling them in 2015 ahead of the ongoing credit tightening, regulatory interference, reputational damage and housing downturn would have been timely. Selling when it cannot get better and buying when the outlook feels bleak tends to be emotionally difficult, but when based on thorough analysis is financially rewarding.

DISCLAIMER: Issued by Platinum Investment Management Limited ABN 25 063 565 006 AFSL 221935, trading as Platinum Asset Management (‘Platinum’). The above information is commentary only (i.e. our general thoughts). It is not intended to be, nor should it be construed as, investment advice or any form of financial product advice. It has not been prepared taking into account any particular investor’s or class of investors’ investment objectives, financial situation or needs, and should not be used as the basis for making investment, financial or other decisions. Before making any investment decision you need to consider (with your professional advisers) your particular investment needs, objectives and financial circumstances. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted by Platinum or any other company in the Platinum Group®, including any of their directors, officers or employees, for any loss or damage arising as a result of any reliance on this information.