As we entered 2018, the prospects for the global economy were as bright as they had been since the onset of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) over a decade ago. The US economy was growing from strength to strength, with tax cuts on the way that promised an additional boost. China had recovered well from its investment slump of 2014-15. Economic momentum was building in Europe and Japan.

There were a number of risks on the horizon. Many stemmed from rising US interest rates, especially as there were fears of inflation being fuelled by the tax cuts which added stimulus to what was already a buoyant economy. Another concern was how funding the increased fiscal deficit would impact on the US bond market. Further on the horizon remained the question of how the world’s central banks would extricate themselves from their money printing exercises or “quantitative easing” (QE). There was also President Trump’s threat of a trade war, along with other politically inspired skirmishes such as Brexit.

Under the radar of most Western media and commentators were the developments of China’s financial reform. The reform essentially aimed to bring securitised assets – the so-called shadow banking activities – back onto the balance sheets of banks. The goal of the authorities was to tighten up on the speculative use of credit outside of the regulated banking environment. While to our minds this was good policy, we did highlight in our March 2018 Macro Overview that the reform process gave rise to a risk of tightened credit availability which could potentially impact the economy. Our base case at the time was that, as China’s economy was undergoing robust growth, the system should absorb and cope with the impact reasonably well.

This assumption turned out to be overly optimistic. The Chinese economy did progressively slow throughout 2018 in response to tighter credit conditions, with notable credit losses occurring in unregulated peer-to-peer lending networks, impacting consumer spending. The slowdown was further exacerbated by the commencement of President Trump’s “trade war” in July. As we have highlighted in past reports, while the impact of the tariffs imposed to date has been relatively minor, they have certainly damaged business confidence and resulted in cut-backs in investment spending in China’s manufacturing sector. The slowdown in China has continued throughout the latter months of the year, with passenger vehicle sales down 13% and 16% from a year ago in October and November 2018 respectively, and the first 11 months of the year registering a 2.8% decline from the same period in 2017.[1] Similarly, mobile phone sales volume in China in Jan-Nov 2018 decreased by 8% year-on-year.[2] Other indicators, such as the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), also registered declines over the last quarter.

The impacts of China’s slowdown have been felt far beyond its borders. While China today is the world’s second largest economy (US$12 trillion versus the US at US$19 trillion), it is for many goods the world’s largest market. Not only is this the case for commodities and raw materials, such as iron ore and copper, it is also the case for many manufactured goods, from cars to smartphones to running shoes. Indeed, it would be difficult to think of a physical good for which China is not the biggest consumer in volume terms. As a result, China’s slowdown has been felt globally and has been a significant factor in the loss of economic momentum in Europe, Japan and many of the emerging economies. The one country that has so far appeared immune to China’s slowdown is the US, which was growing faster in the first instance, but also had the benefit of a fortuitously timed fiscal stimulus in the form of tax cuts.

Prospects for 2019

Reasons for Caution

The loss of momentum in China, together with the trade war, will continue to cause a significant deal of uncertainty. Many companies entered 2018 with strong order books. As is typical in times of boom, customers were likely double-ordering components or items which they thought might be in short supply. When business slowed, these customers would have found themselves cutting back on new orders aggressively. In addition, the trade war also led some companies to bring forward orders to avoid the added cost of tariffs. All of this has created a significant amount of noise in sales outcomes for many businesses and it may well be some time into the new year before one has a clear sense of where demand has settled for many goods. And, of course, we are yet to see whether the US and China can negotiate a compromise on trade prior to the 1 March deadline – when, absent an agreement, US tariffs on a further US$200 billion of Chinese imports will take effect.

More importantly, the greatest risk facing the global economy is that the last driver of growth, the US, is now poised to slow. Housing and auto sales have fallen in response to higher interest rates. The benefits of the tax cuts have for the main part been expressed. The impact of tariffs on business is now being felt. While their direct impact on the US economy is perhaps not significant, the tariffs and the broader trade tension likely have begun to affect both consumer and business confidence, particularly as we await the outcome of the US-China negotiations.

Furthermore, the political environment in the US post the mid-term elections is also likely to be a drain on confidence, and the partial shutdown of the US government over funding debates may well be a prelude for what is to come. While similar shutdowns have occurred in the past with relatively minor disruptions, they certainly add to the distractions faced by both businesses and consumers. President Trump’s infrastructure program could potentially be the next boost to growth, though it is unlikely to have much impact within the next 12 months even if it were to eventuate. As for interest rates, while the Federal Reserve has signalled that it will slow the pace of rate hikes, rate cuts appear a distant prospect. Many commentators have been focusing on the likelihood of a US recession, but it is beside the point. The conditions are in place for a progressively slower environment in the US throughout the course of 2019.

An important lesson from the last four years is that a maturing Chinese economy has become more responsive to domestic interest rate movements and credit condition. As the financial reform started to take hold in 2017, interest rates did rise and the Chinese Yuan appreciated, which subsequently saw economic activity slow in 2018. This is not dissimilar to what happened in 2015 when a recovery in activity from the prior investment slowdown was building momentum, only to be extinguished as capital outflows under the country’s managed exchange rate mechanism led to tightened monetary conditions. Absent a more flexible exchange rate mechanism, China will likely remain susceptible to these mini booms and busts.

Another lesson from 2018 was how important China had become to the global economy. For the last 30 years or more, the US economy and financial markets have been at the centre of every analysis of global markets. It has long become a cliché to say that “when the US sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold”. In 2018, the US economy was in great shape, and yet the rest of the world slowed, because of China.

Reasons for Optimism

Applying these lessons to the year ahead, we would make the following observations. In order to alleviate the stress the financial reform has placed on the system, China has pushed out the deadlines for banks to comply with the requirement to bring their shadow banking assets back onto the balance sheet. Banks’ capital reserve ratios have been cut to free up lending capacity, and funding has been assured for approved infrastructure projects. By October 2018, the 1-month Shanghai Interbank Offered Rate (SHIBOR) had fallen to 2.7% from 4.7% at the start of the year, and anecdotally the availability of credit for companies with strong balance sheets has improved dramatically. Tax cuts are on the way for households and businesses, which are estimated to be in the order of 1% of GDP.

These are important developments that are worth paying attention to. If China’s economy slowed in response to a tightening of credit conditions, one should also expect to see activity gradually pick up as policy loosening takes effect. As it happens in any economic downturn, there will be debates around whether enough has been done and how long before the economy responds. Nevertheless, policy is clearly moving in a direction to, at least, gently encourage growth. Certainly, the broader economic data is yet to show any obvious signs that a bottom has been found, though some “green shoots” can be observed in improving construction equipment sales and a pick-up in infrastructure investment.

Besides the potential for a recovery in China, the other positive that may unfold is a resolution, at least in part, to the trade conflict between the US and China. In our last quarterly report we discussed in some detail the reasons that we believed there were significant incentives for both sides to find a compromise. Subsequently, the 1 January increase in US tariffs from 10% to 25% on US$200 billion of Chinese imports has been deferred while the two sides look to negotiate a deal. In our view, the need for both countries to find a middle ground is compelling, and it also appears that post the mid-term elections in the US, there is now an imperative for President Trump to win a domestic political victory. However, given the innumerable unknowns around the incentives on both sides of the negotiating table, it is difficult to have a strong level of conviction in this view. Presumably, we will be entertained by a “made for TV” style drama as the 1 March deadline approaches.

Market Outlook

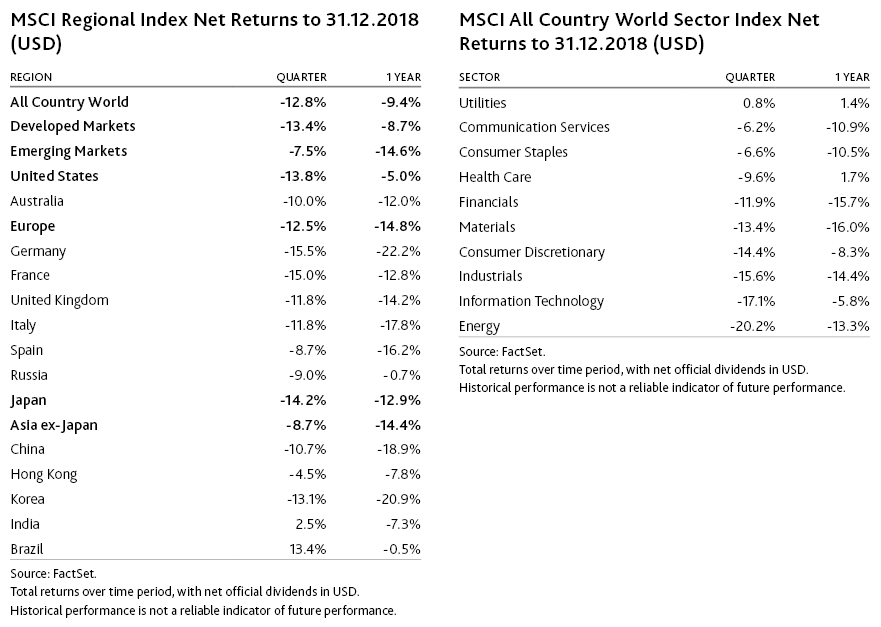

As we observed in last quarter’s Macro Overview, the slowdown in China, the uncertainty around trade, and rising interest rates in the US, had resulted in falling stock prices across the sectors that are sensitive to economic growth or exposed to trade issues. On the other hand, companies that were perceived to be immune to these concerns had performed strongly. These good performers were found primarily amongst high-growth companies in sectors such as software, e-commerce and biotech. Again, as we noted, these high-growth stocks were either at or approaching valuations that were exceedingly high by historical standards. Through the first nine months of 2018, the performance of these sectors accounted for much of the performance differential between the US market, which had continued to reach new highs, and the world’s other major markets, which had been in steady declines since February. In the last quarter, in response to higher interest rates and tightening liquidity, this pattern changed with the US selling off in line with or even more fiercely than other major markets, led by the highly valued tech and biotech names.

Recently Bloomberg recorded an interview with Stan Druckenmiller, one of the most successful hedge fund managers of all time. The hour-long interview covered a wide range of topics, but of particular interest is Druckenmiller’s observation that the signals he has relied on over the last 40 odd years to make calls on markets are no longer working. Druckenmiller noted that interest rate moves during a period of quantitative easing and very low rates, as well as stocks’ price movements in response to news, could no longer be reliably reverse-engineered to give readings on what is happening in the economy. The result has been a higher degree of difficulty in extracting returns from markets. His comments echo those we have read from other experienced fund managers, and indeed in recent years many managers with strong long-term records have performed poorly with quite a number of them choosing to close shop and cease managing money. It is part of the phenomenon of active managers struggling to outperform the market and what some have referred to as the “death of value investing”.

Various reasons have been offered for this idea that markets aren’t behaving quite as one expects. At the top of this list of reasons is the impact of QE and low interest rates. Especially topical at the moment is the question of how the reversal of QE, with the Federal Reserve reducing its holding of US Treasuries, particularly at a time of rising fiscal deficits, is impacting on markets. Another oft-cited reason for recent market “anomalies” is the “rise of the machines” – be they high-frequency algorithmic trading or quant-based investment strategies.

Furthermore, with the rise of populist governments across the world, political risk, at face value, is much greater than it has been. Accumulation of high levels of debt in certain sectors of the global economy may also be playing a role, though this is hardly a new phenomenon. It may simply be that China is having a much greater influence on the global economy and on markets than ever before.

We would broadly agree with the claim that markets are not behaving quite as one expects. However, the reality of markets is that they often don’t behave in line with investors’ expectations, and the patterns that investors think they see are only temporary. So, as investors, how should we navigate our way through this environment? There are two core principles which underpin Platinum’s investment approach. First is the belief that the best opportunities are often found by looking in the out-of-favour areas and avoiding the popular ones. Secondly, the price we pay for a company is the single most crucial determinant of the return that we will earn on the investment.

Guided by these core principles, we would make the following observations about the current state of the markets. Investor sentiment has deteriorated significantly over the last quarter. Sentiment is difficult to gauge with precision, but a number of the quantitative indicators that we use to objectively measure sentiment are certainly pointing to a bearish stance by equity investors. Our more qualitative assessment is that across the markets the level of bearishness varies dramatically by region and by sector. For example, North Asian domestic investors are generally very negatively disposed towards their own markets, and investors are quite fearful of certain sectors, such as autos, semiconductors and commodities, as they are perceived to be more prone to the cyclicality of economic activity. Such observations lack precision and certainty. Of course, if the US economy deteriorates significantly or if the trade talks fall over, it is readily conceivable that markets will fall further. Nevertheless, it is in these periods of great uncertainty that one should be looking for opportunities to buy markets. Our sense is that markets may not have quite bottomed just yet.

At turbulent times like this, we will fall back to an assessment of the potential returns implied by the valuations of our holdings. Simply put, we will consider the earnings or cash flow yields that our companies will provide investors with over the next five years and beyond. While there is no certainty regarding these future earnings, and the prospects of some of our holdings over the next one to two years may have diminished from what might have otherwise been expected, the valuations across these out-of-favour sectors are highly attractive today.

Attractive valuations (i.e. low prices relative to prospective earnings) are not a guarantee that stock prices will not fall further, especially over the short-term. However, the expected returns from an investment are not some ethereal concept – returns will flow to investors’ pockets where companies pass their earnings onto shareholders in the form of dividends and/or stock buy-backs. Alternatively, at the right price, knowledgeable buyers may appear and buy out the company from shareholders. In short, based on our assessment of the current valuations across the companies we own, we believe that our portfolio offers good prospects of favourable returns. What we feel less certain about, however, is the time frame over which these returns will be realised, which is difficult to assess given the numerous challenges facing the market today.

[1] www.marklines.com/en/statistics/flash_sales/salesfig_china_2018, based on data compiled by the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers.

[2] www.counterpointresearch.com/china-smartphone-share/

DISCLAIMER: This information has been prepared by Platinum Investment Management Limited ABN 25 063 565 006 AFSL 221935, trading as Platinum Asset Management ("Platinum"). It is general information only and has not been prepared taking into account any particular investor’s investment objectives, financial situation or needs, and should not be used as the basis for making an investment decision. You should obtain professional advice prior to making any investment decision. The market commentary reflects Platinum’s views and beliefs at the time of preparation, which are subject to change without notice. No representations or warranties are made by Platinum as to their accuracy or reliability. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted by Platinum or any other company in the Platinum Group®, including any of their directors, officers or employees, for any loss or damage arising as a result of any reliance on this information.