Excerpt from a speech presented by Douglas Isles, Investment Specialist at Platinum to the Investment Data & Technology Summit, 21 August 2019. Douglas made the case for ‘man and machine’ in investing rather than ‘man or machine’. Human input is critical when making long-term investment decisions – machines are better suited to winning the ‘race to zero’ – but data is essential, and machines can help with prioritisation and saving time.

As a fundamental equity investor, our business relies on generating superior returns to the market. The elusive search for ‘alpha’ is our bread and butter.

Funds management businesses are straightforward: develop an investment strategy; raise capital to invest on clients’ behalf; and demonstrate competence to maintain clients and attract more. Things fall down when outcomes don’t match expectations.

There’s a big impediment to success. Investing is about solving a long-term problem, but short-term results are published continuously. Investor and manager time horizons don’t always align. Good performance attracts customers. However, they are inclined to leave when things get tougher.

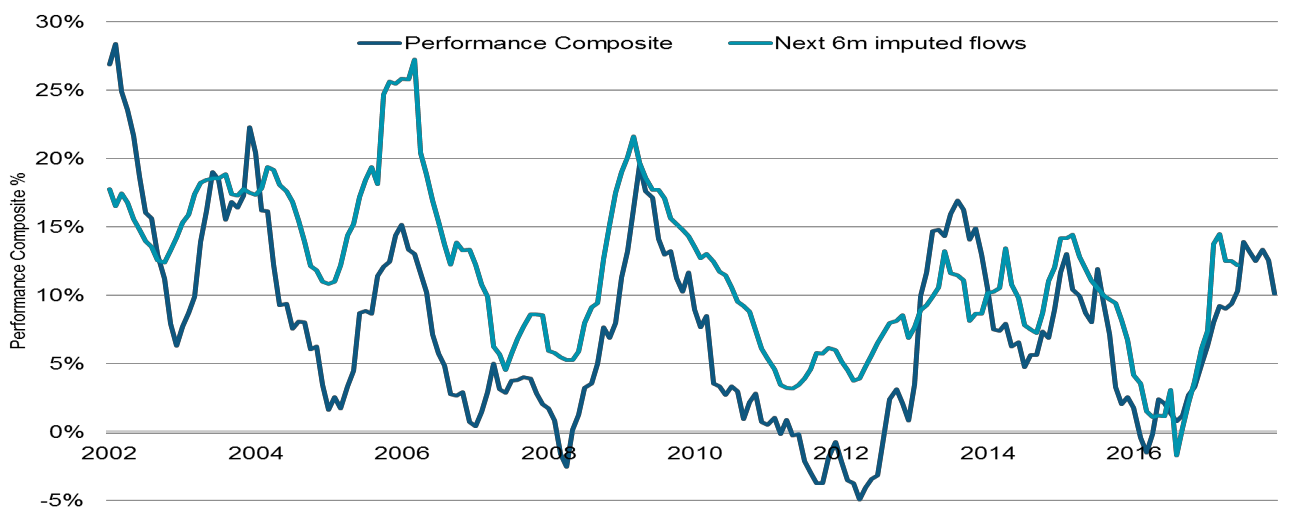

Several studies and our own experience bears this out. It’s startling to chart the performance of the Platinum International Fund with flows (see Fig. 1). When performance is strong, net flows increase. When performance softens, net flows fall.

Fig. 1: Performance vs. Flows - Platinum International Fund

Source: Platinum Investment Management Limited, FactSet.

Performance Composite: Average of 1- and 3-year absolute & relative returns (to MSCI AC World Index)

Imputed flows: Sum of NAVt – NAVt-1 * Monthly return; for the 6 months following composite result

NAVt: Publically available month-end Net Asset Value as at time, t

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future returns.

Keeping up with strong bull markets has proven to be a challenge for many fundamental equity managers. In aggregate, money is flowing from active managers to passive managers.

Data from SPIVA (S&P Indices Versus Active) showed that in 2018, 80% of Australian equities managers underperformed the market over the previous five years.

The three challenges facing active managers are:

1) Fees: The fee is a hurdle to overcome in delivering market returns, or better.

2) Cash: Active managers often carry some cash – to manage risk or to provide flexibility. In rising markets, cash acts as a headwind.

3) Momentum: In bull markets, the theme propelling the market tends to be over-hyped. Many active managers will shun expensive stocks and will thus tend to underperform.

After a 10-year bull market, the case for active management has weakened substantially for many investors.

Passive investing is a systematic process of buying stocks using a particular rule. This may be index replication, or ‘smart beta’ where promoters isolate factors expected to generate superior outcomes to markets. An example might be buying high growth stocks.

Systematic approaches champion low fees. Their efficiency fires a warning shot, even for genuinely active managers. Index-huggers will have fees crunched or die. It demands active managers have an edge that is not replicable or ‘code-able’.

The emergence of passive investing is similar to the disruption that is hitting every industry. Indeed, many active managers fear for their existence.

Passive investing is the implementation of a rule. It promotes the case for automating investment management. As the bull market continues, the case to replace active managers with spreadsheets gets louder. It’s not a sophisticated approach – efficiency wins and the lowest-cost provider dominates. No skill is involved. It is man vs. machine, but we’re not referring to Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Complexity is inherent in active/fundamental investing

Conversely, active, or fundamental investing, is about outwitting the market. The efficient market hypothesis suggests prices reflect all available information.

In 1997, we were all impressed when a computer beat World #1 Garry Kasparov at chess. 20 years later, a machine won at another board game called Go, against the less well-known World #1 Ke Jie. Many feared that the singularity was near. Unlike the finite nature of chess, Go was seen as unbounded, unsolvable. But it does adhere to a strict set of rules.

Our existence as active managers requires us to exploit uncertainty, disagreement and complexity. Machines will replace those investors who simply agree with the market.

However, just because a fund manager exists doesn’t mean it has an edge. Finding the rare and genuine edge to deliver long-term performance is the goal of fund selectors. But, for a fund manager to survive – an edge is essential.

We see our edge primarily as the mentality applied to our process.

Our process is based around understanding our biases and counter-acting them. It’s about controlling our emotions, and exploiting the emotions of others (in a non-malicious way).

Our solutions are to avoid the crowd, explore change and think like a private owner; we detach ourselves from predicting share price moves. These solutions are hard to specify and to code for a machine to follow.

Taking on the crowd is uncomfortable. A machine could help with the detachment from emotional pain, but detachment from pain is not enough. One requires critical reasoning, far beyond the realms of AI, to determine whether to invest. So it’s one thing to know where the crowd is, but it’s another to know if it should be there or not.

We ask our curious people, who love business, to have a debate. We take a multi-year view on where a business is going, and we make this judgement using critical reasoning and drawing on the experience of our team, and their networks. I would suggest that coding this would be nigh on impossible.

Kasparov’s book, Deep Thinking, describes his experience of being the World No. 1 who lost to a chess machine. He concludes that man and machine in combination is more powerful than each alone.

Platinum has been in business since 1994. We describe our search for ideas as using “themes and screens” - combining man and machine. Themes arise from developing domain knowledge. This might include concepts like emerging Chinese consumers, demographics or mobile data. The screening process uses quantitative filters. Data can narrow the vast universe of companies to those that merit further investigation.

The key purpose of screening is prioritisation. We acknowledge there are too many companies for humans to determine the most attractive one easily. The screening process shortens the research list for the team, recognising analytical resources are scarce.

For quant firms (i.e. those that make investment decisions based on quantifiable data), screening is everything. They identify a small edge, and then exploit it across huge ranges of stocks. Various techniques are used to size positions and diversify specific risk.

For fundamental investors, screens are simply a starting point – they uncover stocks for analysts to potentially interpret things differently to the market.

Screening, whether the starting point or sole purpose, will likely revolve around three dynamics: Value, Quality and Momentum.

1) Value explores whether a share is cheap or expensive. It relates price to fundamental factors like earnings, revenues or assets. It is generally accepted that buying cheaper stocks makes sound investment logic.

2) Quality considers how good underlying businesses are – generally via profitability. It is generally accepted that buying higher-quality stocks makes sound investment logic.

3) Momentum looks at rates of change. This could be in stock prices, or in fundamentals like earnings or sales. Analysis suggests that in the short term, buying stocks with momentum is a sensible investment strategy.

The Holy Grail is to find an excellent business with improving earnings at a bargain share price. However, professional investors know that, and hence they tend to want to buy the same things. In reality, various compromises need to be made.

Platinum’s philosophical approach is to avoid the crowd. Using a Value/Quality/Momentum framework, we can seek more value for given levels of quality. We generally must sacrifice short-term momentum to get that. This increases our discomfort, hence the mentality is key, and it works over time, but it is not dogmatic.

In the fundamental approach, screens can have varying degrees of sophistication. The goal is to stimulate the analyst to look at companies they would not find from their general observations. The key is exploring why companies appear and then determining if further research is merited.

Having decided to work on an idea, the analyst draws on their domain knowledge, and that of their colleagues. Many additional data sets then also come into play in analysing the drivers of a company’s performance.

We look at the relationships between a company’s performance and various data series. For example, for a company like BHP, we consider commodity prices. More recently, we also look at web-scraped data. YipitData provides web-scraped data that might show us, for example, what’s being sold on Alibaba. This still requires interpretation, but is the modern version of analysts sitting outside a shop, counting customers. Satellite data can also be acquired to look at things such as supermarket car parks, or container ports, for example.

So, we still rely on critical thinking, asking the right questions, and triangulating the views of customers, competitors, industry experts and suppliers.

All data sets do, from a fundamental perspective, is help us obtain a clearer and deeper understanding of what drives companies. As fundamental investors, we are trying to reduce the risks of being wrong in assessing portfolio investments.

AI, constantly touted as threatening knowledge businesses, is simply multiple regression. It detects patterns from data. To do that efficiently requires quantifiable data. To progress from here, we need to quantify things like annual reports and transcripts. But analysis requires critical thinking. AI cannot see around corners - it can only draw on the past.

Where most data is quantifiable and critical reasoning is the hardest, is over the shortest time-periods. Enter the domain of high frequency trading - taking very short-term positions to harvest minute gains. Data is readily available on bids, offers and transactions in terms of prices, sizes and changes. Algorithms can be developed to derive signals from this. As time horizons lengthen, it gets harder to quantify everything. We can argue that it is neither practical now, nor will it be in the foreseeable future.

Over a year, changes in market sentiment have more influence on returns than fundamentals. For longer periods, say three years or more, it’s about understanding earnings drivers. This is in a constantly changing world, affected by technology, regulation, consumer tastes and competitive responses. Quantifying and performing multiple regression on googols of data still fits data to historic patterns, and misses the critical reasoning required to properly assess the impacts of never-seen-before changes, and underestimate the complexity of the business landscape.

The role of our trading teams is to execute orders that come from analysts’ work driving portfolio managers’ decisions. Mechanical and automatic participants are widespread and they must understand the impacts from algorithms, quants, high frequency traders, and passive investors. The human touch remains helpful for sourcing liquidity. This is aided by information systems, but there remains relationship aspects to knowing who is doing what – commentary, written, or verbal, gives clues to where buyers and sellers are, and their intentions.

The growth in passive investing has changed the profile of liquidity throughout the day in markets – much more of the volume is near the market close due to these funds’ behaviour. This changes trading patterns and increases the risk of market manipulation.

There is a race to zero in trading. Zero distance from exchanges, zero latency, zero holding periods, and zero fees. But this race to zero is very expensive. We don’t want to play in that arena. It’s necessary to be aware of it, and indeed try to exploit it. With a battleground at zero (a zero-sum game), we surely must compete elsewhere.

Our edge is critical reasoning and mentality. Our curious, business-loving analysts’ debate is not programmable.

Zero is not where we play. Instead, our pay-off unfolds over time. We focus on longer-term perspectives and understanding human behaviour, human endeavour, and humans’ ability to change and evolve.

Markets are human constructs, human meeting places, and aggregations of human opinions. Investment portfolios are far more complex than Chess or Go. Today, humans still have a distinct advantage as investors. Machines cannot see around corners. But, using data and technology we can enhance our efficiency and better allocate our scarce human analytical resource. Together, man, assisted by machines, can strive to get the best possible client outcomes.

DISCLAIMER: This article has been prepared by Platinum Investment Management Limited ABN 25 063 565 006, AFSL 221935, trading as Platinum Asset Management (“Platinum”). This information is general in nature and does not take into account your specific needs or circumstances. You should consider your own financial position, objectives and requirements and seek professional financial advice before making any financial decisions. The commentary reflects Platinum’s views and beliefs at the time of preparation, which are subject to change without notice. No representations or warranties are made by Platinum as to their accuracy or reliability. To the extent permitted by law, no liability is accepted by Platinum for any loss or damage as a result of any reliance on this information.